Winners of the President’s Award, presented annually at the end of the Archie League Medal of Safety Awards Banquet:

2024: Southern Region: Steven Brader, Nashville ATCT (BNA), William Mitchell (BNA), and Jaime Romaker (BNA)

At #NATCACFS 2024’s Archie League Medal of Safety Awards program tonight, the 2024 President’s Award, the highest honor for a flight assist, has been awarded to the Southern Region team comprising Steven Brader, William Mitchell, and Jaime Romaker of Nashville ATCT (BNA) for their exceptional handling of a critical situation. The pilot, facing deteriorating weather and low fuel, relied on the quick thinking and expert guidance of these dedicated professionals. Their coordinated efforts to locate a safe landing spot and guide the pilot through challenging conditions ultimately ensured the safe landing of the aircraft at John C. Tune Airport. This extraordinary act of skill and dedication was recognized as the best flight assist of the year by NATCA President Rich Santa.

Read the full story of this flight assist.

Watch the Award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Listen to a conversation with these three NATCA members.

2023: Chip Flores, Fort Pierce ATCT (FPR), and Robert Morgan, Palm Beach International ATCT (PBI)

Each year the NATCA President selects for the President’s Award the most outstanding flight assist of the year. As part of Communicating For Safety 2023 and during the 19th annual Archie League Medal of Safety Awards Banquet, NATCA President Rich Santa selected 2023 Southern Region Archie League Medal of Safety Award winners Chip Flores (Fort Pierce ATCT, FPR) and Robert Morgan (Palm Beach International ATCT, PBI) as the 2023 President’s Award recipients.

Read the full story of this flight assist. https://www.natca.org/community/awards/2023-archie-league-medal-of-safety-award-winners/#NSO

Watch the Award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Listen to a conversation with these three NATCA members.

2022: Megan Baird, Fort Worth Center (ZFW), and Kerri Fingerson, Boston Center (ZBW), formerly at ZFW

Article by Mary Ann Hall (Houston Hobby ATCT, HOU)

On April 23, 2021, the skies over Oklahoma were riddled with areas of precipitation and low ceilings. At 4:51 p.m., N7108Q, a Cessna 172, executed a missed approach at Clinton Regional Airport (CLK). He immediately requested another RNAV approach onto Runway 17. Fort Worth Center (ZFW) member Kerri Fingerson (formerly Phillips) was working a low sector in the Bowie Specialty. She did what every controller would do – radar ID, clarified his intentions, and cleared him back to Clinton Regional. Kerri did ensure the pilot had the most recent weather report which included a visibility of 1.5 nautical miles and an overcast ceiling at 400 feet.

Soon after Fingerson cleared and switched N08Q to advisory, she called the tower at neighboring airport to the west, Clinton-Sherman (CSM), to ask about its current weather conditions. The airport was socked in. She inquired north to Kansas, farther west to Elk City (ELK) and south to Wichita Falls (SPS) – all reported low ceilings. Will Rogers Airport (OKC) to the east had better weather conditions, but heavy to extreme precipitation stood in the way. It was then that N08Q missed again.

“I had that ‘Spidey’ sense – that tingling feeling you know – that something just wasn’t right,” Fingerson recounted.

Instead of flying the published missed approach, which is runway heading for 12.5 nautical miles and climbing to 4,000 feet, the pilot made a sharp left turn and checked in with departure at only 2,800 feet.

“I knew at that point that he knew he was in trouble even though he really hadn’t admitted it verbally yet,” Fingerson said.

She immediately informed the pilot that minimum IFR altitude was 4,000 feet and instructed him to climb and fly the published missed. No response. She gave the instructions again, and he finally responded.

22:27:23Z: “N7108Q…do you need any assistance?”

22:27:29Z: “Eh…we…uh…we are getting set up.”

22:28:17Z: Kerri informed the pilot his heading was better and proceeded to give airport weather reports.

22:29:04Z: “Okay we have about 50 minutes of fuel left. Uh we need to do something quick.”

Fingerson acted immediately and got on the phone with Sheppard Air Force Base-Wichita Falls Municipal Airport (SPS) to verify its ceiling improved to 1,200 feet overcast. Once she received confirmation, she was back with N08Q to relay that option. The pilot initially said that he was only in a C172, and he would, “try this one more time here and I’ll make her in.” Fingerson knew that was not a good idea.

With the pilot being in a slow-moving Cessna, she informed him that SPS was about 90 miles to the south and with only 50 minutes of fuel remaining he would be short on options if he failed the third approach. The pilot agreed. Not only was the weather against them, but now so was time.

ZFW member Megan Baird was coming back from break but was not assigned a position yet. She had overheard Fingerson and sensed she might need assistance, so she plugged in next to her and asked what she could do to help. Together they called around to find better weather reports and PIREPs. A call to Fort Sill Approach determined the Lawton Airport (LAW) had an overcast ceiling at 500 feet and Duncan Airport (DUC) had a scattered layer at 800 ft and an overcast ceiling at 1,200 feet. While still 75 nautical miles away, Duncan became the new objective.

Fingerson and Baird got back on the line with Fort Sill Approach to request shutting down the restricted area that laid between Clinton Regional and Fort Sill’s airspace, so N08Q could fly the quickest route. As the pilot made his way southeast bound, the controllers were still calling to get weather reports at closer airports, but Duncan remained the best option. The pilot reported two souls on board and since he was flying more efficiently, he now had 60 minutes of fuel, but it was about a 44-minute flight to Duncan.

Fingerson had been waiting on a PIREP from an Envoy making an approach at Lawton Airport. Once the aircraft landed, she learned the bases were 2,000 feet. Lawton is 35NM closer than Duncan, so they changed course. Fingerson offered a higher altitude for fuel conservation, but N08Q decided to maintain his current altitude of 4,500 feet. Next, she vectored him towards LAW VOR, and later switched him to Fort Sill Approach. 22 minutes after the switch and with only about 14 minutes of fuel remaining, N08Q landed safely at Lawton Airport after flying a surveillance approach.

“Kerri’s decisive action, clear communication, and potentially lifesaving recommendation ensured the successful outcome for the crew of N7108Q,” said Joel Hays, Fort Worth Center NATCA Vice President.

When asked if there was any training that helped prepare her for this event, Fingerson responded that back in 2019, Women for Aviation International (WIA) hosted a breakfast during AirVenture at OshKosh, and the guest speaker was Tammy Jo Shults (also a speaker at this year’s CFS).

Fingerson said that Tammy is very inspirational and quoted her saying, “Habits become instinct under pressure.” That statement resonated with her. Fingerson recalled her first trainers and how they instilled good practices in her from her early years as an air traffic controller, and she continues to learn with recurrent training.

“All of that really paid off – those habits that you develop during training – they do become instinct,” Fingerson said.

Fingerson and Baird are the 11th and 12th ZFW members to win the Archie League Medal of Safety Award, joining Chris Owen in 2005, LouElla Hollingsworth in 2013, Phil Enis, Thomas Herd and Hugh Hunton in 2018, Larry Bell, Brian Cox, and Colin McKinnon in 2020, and John (Randy) Wilkins and Christopher Clavin also in 2020.

“Kerri has worked to elevate the safety culture at ZFW through her work on the LSC. She put her talents and lessons learned into action and provided critical information to ensure the best possible outcome for N7108Q. At ZFW we emphasize being a team player – see something, say something. Megan exemplified this mantra when she took swift action to help Kerri in a very difficult scenario. Megan’s actions show that we are part of the ultimate team sport and set an example of embracing that very important concept.”

– Nick Daniels, Southwest Regional Vice President

Watch the Award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Listen to a conversation with these three NATCA members.

2021: Jeremy Hroblak, Los Angeles ATCT (LAX), Scott Moll (LAX), and CJ Wilson (LAX)

Around 3:30 a.m. on Aug. 19, 2020, the crew of FedEx Flight 1026 (FDX1026), on approach to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), notified LAX member Scott Moll that they needed to conduct a go-around due to an unsafe landing gear indication. As any tower controller can tell you, this isn’t uncommon and usually ends with the pilots taking a little time to work out the issue and then returning for an uneventful landing.

With that in mind, and adhering to normal procedures, FDX1026 was vectored out over the Pacific Ocean to work the problem. At this point, numerous challenges began to present themselves for this flight. The first was relatively small. After some time, the pilots asked for a low approach at 1,000 feet over the runway to get a visual confirmation as to the status of the gear. But the darkness and the height of the aircraft above the tower made it nearly impossible to confirm what Moll and his ground controller, CJ Wilson, thought they saw. The left main landing gear appeared to be retracted.

Moll began to coordinate a second low approach with Southern California TRACON (SCT), this time at 300 feet above the runway. Wilson and Moll coordinated with airport operations to get vehicles on the field, and with another FedEx crew that had just landed, to assist in visually inspecting the landing gear to ensure as many eyes as possible would be on that aircraft as it made a low approach. It was confirmed: the nose and right main gear was down but the left main gear was still up.

Another large challenge appeared at this point. Having exhausted all their options, the crew of FDX1026 determined they would have to attempt an emergency landing. The two controllers knew that the workload in the tower was about to increase exponentially. So, they recalled Jeremy Hroblak back from his break to conduct the immense amount of coordination and communication associated with the controller in charge position.

The crew of FDX1026 requested the longest runway at LAX, runway 25R. But another challenge presented itself because the runway was closed due to the city venting gas from a complex on short final for that runway. None of the three controllers on duty that night had ever seen the city do this venting procedure before, or since. But on that night, it had an impact.

When Hroblak arrived in the tower, he coordinated with the city to halt the venting and make runway 25R available for the stricken Boeing 767.

Yet another issue had been lingering for nearly a week prior to Aug. 19. The crash phone, used to summon the Aircraft Rescue and Fire Fighting crews, was out of service, which complicated the required, and urgent, Alert 2 notification. An Alert 2 indicates that an aircraft is having major difficulties. Jeremy got in contact with the fire captain on his personal cell phone and utilized that means of communication throughout the event.

An immense amount of coordination occurred over the next few tense minutes leading to FDX1026 making an emergency landing on runway 25R, just after 4 a.m. The flight crew abandoned the aircraft on the runway due to the potential for fire, and both survived, though one did suffer a broken leg while using the escape ladder.

Despite the numerous challenges presenting themselves, Moll, Hroblak, and Wilson, through their skill and professionalism, were able to address them all, contributing to the most successful outcome possible.

The captain of FDX1026, Bob Smith, wrote a letter describing the event from his perspective. He concluded the letter by saying, “As we say at FedEx to a team member for a job well done … Bravo Zulu! Thank you for your professionalism, and for your significant contribution to an aircraft incident that, because of your actions, ended with a safe landing and minimal damage to our aircraft.”

NATCA is happy to report that the crash phone was repaired the very next day.

This is the second Western Pacific Region Archie League Medal of Safety Award-winning event from LAX, joining Michael Darling’s award-winning save in 2007.

Watch the Award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Listen to a conversation with these three NATCA members.

2020: Marcus Troyer, Pensacola TRACON (P31)

It was like most any other ordinary summer afternoon in Pensacola, with a lot of weather, when Marcus Troyer plugged in for his shift at Pensacola TRACON (P31) shortly after 12:30 p.m. EDT. In the skies to the west, U.S. Coast Guard Lt. Commander Brian Hedges was the pilot and aircraft commander on an ordinary training mission in a newly-converted MH65E helicopter. But a short time later, Troyer and Hedges were joined in a search and rescue effort that was anything but ordinary and showcased the essential nature of their respective professions.

Thanks to their efforts, the life of the pilot of a Cessna 172 Skyhawk, Scott Jeffrey Nee, was saved after he crashed into the sandy bank of the Escambia River in a remote area of Jay, Fla., north of Pensacola near the Alabama border, and was seriously injured.

“They are heroes,” said the plane’s owner, Freddie McCall. “They saved a man’s life.”

McCall called the facility to report that he was missing an aircraft.

“We weren’t talking to the aircraft at the time,” Troyer said. “We went back and did a Falcon replay to try and see if we actually tagged him up or anything. We did not, so that complicated the situation.” Troyer had experience doing quality control work and was well versed on search and rescue situations.

McCall, who used his own aircraft to look for Nee, located the crash scene and reported that to Troyer, who was in his 12th year of his Federal Aviation Administration career – all at P31 – through this event before initiating a transfer to Houston Intercontinental ATCT (IAH) earlier this year. “I used all my knowledge that I had from working at Pensacola and tried to get Navy helicopters to respond, but most of them couldn’t do it because of fuel,” he said, adding that the heavy thunderstorms in the area posed many challenges. A LifeFlight crew was in Pensacola but had just completed a mission and was in a mandatory cool down period.

Soon after, Troyer contacted Mobile ATCT (MOB) and asked if they were providing service to any Coast Guard helicopters. He did this because he knew that the Coast Guard has a base in MOB airspace. However, that base is used strictly for training and aircraft testing, not search and rescue. A MOB controller advised Troyer they were talking to a Coast Guard helicopter and he requested them to switch the communications to Troyer’s frequency. Troyer made contact with Hedges (pictured above), explained the situation, and asked if they would voluntarily attempt to respond to the crash site.

“I felt like if anybody was going to be able to do a rescue and get this pilot out of there, it was going to be the Coast Guard,” said Troyer, who spent the next 25 minutes vectoring Hedges to the crash site and helped get him around a strong line of storms. At that point, an EMS crew on the ground had reached the pilot and Troyer facilitated communications between them and Hedges.

“We had a very good crew but we didn’t have a rescue swimmer on board so theoretically we were not SAR (search and rescue) capable,” said Hedges, who has over a decade of experience as a Coast Guard pilot. He was joined on board by Lt. Commander Bob Lokar and Petty Officer James Yockey. Their base is the largest Coast Guard aviation training facility in the country. “This was the first search and rescue case in the MH65 Echo aircraft so it was kind of unique. We didn’t plan it that way but our aircraft had an all-new glass cockpit and brand-new weather radar, which actually helped us that day.”

Hedges said the unplanned SAR operation was made much smoother due to Troyer. “His demeanor, everything on the radio, was fantastic,” Hedges said. “He painted a perfect picture of where we needed to go, what we needed to do, and who was on the scene.”

Once they reached the crash scene, Hedges said he had to keep the helicopter running at half power to prevent it from sinking into the soft sand on the riverbank. As it was, he said, the wheels were halfway down into the sand during the brief time he was on scene.

The crew soon took off with Nee and an emergency medical technician on board and headed to Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola. Troyer knew Hedges had never landed at that hospital before so he put him in touch with the LifeFlight pilot who was there and could walk him through the landing and any details he needed to know to arrive safely.

USCG Aviation Training Center Commanding Officer, Capt. W.E. Sasser, Jr., sent Troyer a letter of commendation for what he called Troyer’s “exemplary response.”

“The professionalism and expertise of your team helped my aircrew to safely navigate numerous hazards through the duration of the mission,” Capt. Sasser wrote. “Your controllers were directly responsible for saving a life. I commend your team for their hard work, dedication, and expertise! Bravo Zulu and Semper Paratus.”

After he left position following the event, Troyer said he went to his car to try and relax from the incredible adrenaline rush he was feeling. He said all he could think about was the condition of the pilot, and his desire to talk with Hedges to say thanks. Since the event, he and Hedges have talked several times and gotten to know each other. Troyer said he is appreciative to P31 colleague Dan Briscan for spearheading the effort to recognize him for this save, and had a suggestion for his fellow members who go through these types of events together as a team.

“Show your appreciation to your fellow brother and sister controllers,” he said. “We all say, ‘well, that’s just part of your job,’ but anytime somebody goes through it, the adrenaline’s rushing, people handle things a little bit differently. But talk to them after. Give them some praise.”

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Podcast: Below, hear Troyer and Hedges tell their story, and discuss their efforts to make this rescue mission a success, in an episode of the NATCA Podcast.

View a transcript of the podcast here.

Media: Watch here, a story from WEAR-TV.

2019: Andrew Rice, Chicago O’Hare ATCT (ORD), and Ryan Schile (ORD)

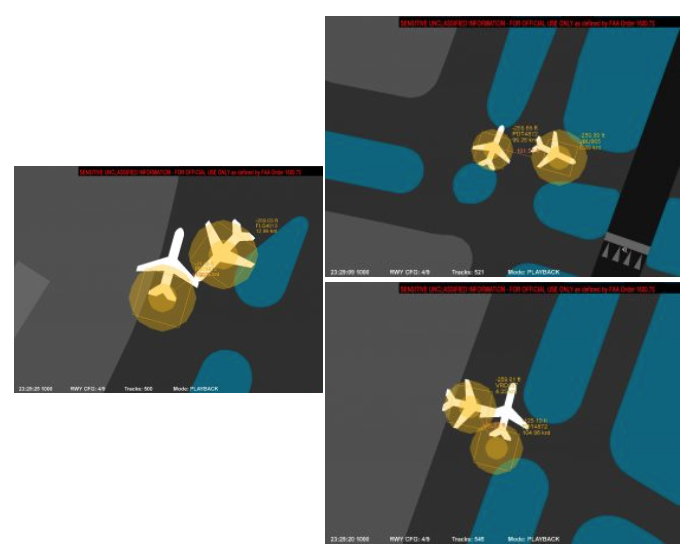

On March 1, 2019, after noon CST, Chicago-O’Hare (ORD) certified professional controller (CPC) Ryan Schile was working third local control and was departing aircraft off of Runway 10-Left at intersection DD. Schile was also working the arrivals that were landing on 10-Right and 10-Center. He worked them back across the runway he was departing to the terminal area.

“Needless to say, he was a little busy,” NATCA President Paul Rinaldi said in introducing the story to the Archie League Medal of Safety Awards banquet on Sept. 18 at Communicating For Safety.

Schile issued a departure clearance to an Envoy Air twin-jet ERJ-145, with an initial heading of 100 and a takeoff clearance. This heading paralleled the departure runways and the arrival runways so there would be no conflict. The pilot of the ERJ-145 read back the correct heading and began takeoff roll.

Once airborne, for an unknown reason, the ERJ-145 began a hard-left turn, placing that aircraft in a collision course with an American Airlines Boeing 737-800, which was departing Runway 9-Right. Schile quickly recognized the potential for a collision and instructed the ERJ-145 to stop his climb immediately.

Subsequently, Schile issued an immediate turn to the right to a heading of 140.

Working on the other side of the airport was fellow ORD CPC Andrew Rice, who was working the American 737. He also observed the impending collision and issued the aircraft an immediate left-hand turn and a 070 heading. Seeing that was not enough, he instructed the aircraft to continue its left-hand turn on a 360 heading to pull these aircraft apart.

The Federal Aviation Administration measured the closest proximity of the two aircraft at .23 nautical miles and 100 feet.

“And that is only because these two controllers acted so quickly to pull these airplanes apart,” Rinaldi said. “Their actions on that day saved hundreds of lives.”

Schile, upon receiving the President’s Award with Rice at the Archie League Medal of Safety Awards banquet, described the way he felt immediately after the event and the knowledge of just how close these two aircraft got before they were saved. It’s not something any controller wants to experience, his words indicated.

“Andy and I are deeply grateful, honored, and completely humbled to receive this recognition,” Schile said. “But respectfully, we hope to hell we never receive it again.”

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

2018 (tie): Phil Enis, Fort Worth Center (ZFW), Thomas Herd (ZFW), and Hugh Hunton (ZFW)

It was an emotional moment on Jan. 10, 2018 when pilot and Paris, Texas, neurologist Dr. Peter Edenhoffer met and thanked the air traffic control team at Fort Worth Center (ZFW) that came to his aid on Super Bowl Sunday 2017 when his Cessna Cardinal experienced complete electrical failure. Hearing Edenhoffer describe how he texted his son to tell him goodbye -thinking he was not going to survive the experience – hit the controllers hard.

But Edenhoffer did survive, thanks to the teamwork and quick, outside-the-box thinking demonstrated by the team of professionals at ZFW with more than 150 years of combined experience: NATCA members Hugh Hunton, Thomas Herd, and Phil Enis, with support from Charlie Porter, Mike Clifton, Mike Turner, and Bryan Beck.

The three NSW Archie League winners and others on duty that Sunday evening had just one hour left on their shifts. Edenhoffer’s flight began uneventfully. He was cleared to land in Paris, which was reporting ¾-mile visibility with 200-foot cloud ceilings. But then Porter and Enis noticed the aircraft’s beacon code reappear on their radar scope. That would not be unusual if a plane missed its approach and was going around for a second attempt, but the altitude indicator showed the aircraft was climbing well above the missed approach altitude of 3,000 feet to as high as 6,500.

Enis attempted to reestablish communications with Edenhoffer without success. He then noticed the beacon code briefly change to 7700, indicating an emergency. Over the next hour, Porter and Enis used every technique they knew to attempt to reach Edenhoffer. They asked other aircraft on frequency to attempt to reach him and continually advised him of his aircraft’s position to emergency airports and more favorable weather conditions for visual flight, even with no response.

The team brainstormed new ways they could reach Edenhoffer, including a Google search of the aircraft tail number. That led to a Google search of the Edenhoffer’s name based off his registrations, which in turn led to finding out he was a neurosurgeon. Then they searched locations where he could possibly practice neurosurgery near the home base of the aircraft, which led to a call to a hospital that knew Edenhoffer. They finally were able to locate his cell phone number. Calls to the cell number for 45 minutes were not answered but then they tried texting Edenhoffer – and it worked.

Texts revealed Edenhoffer not only had suffered a complete electrical failure, but he was flying on minimal fuel and needed to land quickly. “It was pretty tense,” Edenhoffer said. “My worst flying hours that I’ve had.” The team of controllers texted Edenhoffer the VFR areas in his vicinity. He texted ZFW to request they turn the runway lights on at Majors Airport in Greenville, Texas. The controllers tracked him and waited anxiously before receiving a triumphant final text from Edenhoffer that he had landed safely.

To mark the occasion of the reunion, Edenhoffer presented the team with a thank you letter.

He wrote, “How can simple words of thanks ever express the depths of saving a life? There are, however, only words of appreciation, which can be offered. Had your team not been willing to think outside the box, to use personal ingenuity even against the conventional rules in place, I might not be sitting here to write today. So often rules are so ingrained in individuals that they impede even the goals they are designed to reach. Thankfully, such was not the case that night.”

Emotional Reunion as Pilot Meets ZFW Team That Helped Save His Life

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

2018 (tie): Joshua Hall, Memphis Center (ZME), Patrick Allen Johnson (ZME), Jeremiah Lee (ZME), Darren P. Tumelson (ZME), William T. Vaughn III (ZME), and Andrew John White (ZME)

On the afternoon of Friday, Aug. 11, 2017, a Piper PA-31T Cheyenne departed Cleveland, Miss., located between Memphis, Tenn., and Jackson, Miss. The aircraft was en route to Destin, Fla., and the pilot, Charles Schindler, requested VFR flight following. Shortly after reporting on frequency, he stated that there was an issue with the aircraft and he was attempting to troubleshoot.

Within a few minutes, the problems got worse and Schindler declared an emergency. He requested to land at Greenwood, Miss., less than 10 miles away.

The controllers working on Memphis Center (ZME) sector 65, Andrew White and Tommy Vaughn, spent the next two hours assisting Schindler as he experienced locked flight controls, autopilot issues, loss of pitch control, and hydraulic failure. A team of other controllers, including Josh Hall, Patrick Johnson, Jeremy Lee, and Darren Tumelson, and supervisors went to work to assist Schindler with the many issues he was dealing with.

A key moment came when the team contacted Vincent Zarrella, Director of Global Customer Support with Piper Aircraft, Inc. Johnson, who has multi-engine IFR experience, was on the phone with Zarrella and relaying information directly to and from Schindler. Johnson told Zarrella that Schindler could not lower the landing gear and that the aircraft was suddenly experiencing changes in altitude with no command inputs. Schindler could not move the flight controls and he thought the autopilot was engaged. Zarrella brought Piper Chief Pilot Bart Jones into his office and they continued to provide instructions for Schindler on how to disengage the autopilot, including pulling all related circuit breakers and momentarily turning off both generators and the battery. But this didn’t help Schindler’s ability to move the flight controls.

Zarrella and Jones advised Schindler to override the autopilot by forcing the flight controls. Reducing power caused the aircraft to descend, indicating that if autopilot engagement was the problem, at least the altitude hold mode was not engaged and Schindler could control his altitude with power.

At one point, the controllers told Schindler to start a northward turn to avoid a line of thunderstorms that he was approaching while involved in the difficult task of simply maintaining straight and level flight. The aircraft was approximately 80 miles south of Greenwood and the controllers continued to provide navigational guidance, reassurance, and information.

Finally, after more expert guidance on final approach from Zarrella, Jones, and Johnson, Schindler landed safely at Greenwood. It was almost two hours and 300 miles from where he took off. His unintended destination was only 37 miles away from his departure.

This was the second time in 18 months that Schindler experienced an in-flight emergency in the same aircraft in Memphis Center’s airspace and, incredibly, the second time Tumelson was part of the resulting flight assist.

Schindler’s wife, Ashley, who had waited helplessly on the ground during the event, wrote a thank you note to the facility which read, in part, “Probably the most calming for me was knowing that Memphis Center had him! Each and every one of you played a specific role to support my husband and his safe landing and for that, he, our five children, and I owe you a debt of gratitude that cannot possibly be repaid properly.”

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

2017: Eric J. Knight, Boston Tower (BOS), and Ross Leshinsky (BOS)

On the evening of Oct. 20, 2016, Boston (BOS) Logan Airport was set in an uncommon configuration due to weather and low ceilings: Controllers were running ILS (instrument landing system) approaches to Runway 4R, while ILS approaches to 15R were circling to land on 4L.

The tower already was short-staffed, when they got a call from a local hospital that the front line manager’s wife had been in an accident and he needed to leave. (She was not seriously injured.)

A Piedmont Airlines De Havilland Dash 8-300 aircraft was making the circle approach to 4L when the CIC (controller in charge), Eric J. Knight, and LCW (local control west) controller Ross Leshinsky noticed that the aircraft was on an abnormal profile. The aircraft was lower than usual with this approach. Leshinsky noticed the aircraft did not have its landing lights on and asked the pilot to check his gear.

Everyone in the tower kept an especially careful eye on the aircraft as it was on its short base over the channel. The aircraft came in on a short dogleg. When the plane rolled out with less than an eighth of a mile to go, it was actually lined up for Taxiway B instead of 4L. What happened next occurred in a matter of seconds.

Leshinsky: 4872, go around. Go around. Go around now! Go around.

PDT4872: I’m goin’ around 4872.

Leshinsky: 4872 climb and maintain three thousand.

It was Knight who noticed immediately that the aircraft was lined up for the taxiway. After Leshinsky issued the go-around instruction, the aircraft began to pull up and flew over a JetBlue aircraft that was on the taxiway.

The controllers’ teamwork and attention to detail working a busy traffic area prevented a potentially devastating outcome.

New England Region Vice President Mike Robicheau:

“Logan Tower has many unique challenges due to its compact runway space. Being able to identify an aircraft landing at night with no lights turned on is hard enough already, let alone having the ability to immediately identify when the aircraft begins to go off course from the runway to the taxiway. Leshinsky and Knight’s experience and lightning-fast instincts saved lives that day. I am extremely proud of both of my New England Region brothers.”

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

2016: Donald Blatnik III and Kenneth Scheele, Central Florida TRACON

It was a busy push on April 18, 2015, when Donald Blatnik was training Kenneth Scheele on East Departure at Central Florida TRACON (F11). During this training session the pilot of a Cessna 400 suddenly reported low engine pressure and requested to land at the nearest airport.

N400BZ: Daytona, 0BZ, I got an issue with my engine right now, I’m not declaring an emergency or anything like that but I need to get direct to Kilo Tango India X-ray immediately for 0BZ.

Blatnik immediately took over the position and frequency in order to assist the struggling aircraft. The pilot reported that his engine and oil pressure were rapidly worsening and that he needed to get as low as possible. Blatnik continued to work the numerous other aircraft in his saturated airspace and began to direct them out of the aircraft’s way. Blatnik was updating the pilot with the location of nearby aircraft and the distance to the nearest airport, Space Coast Regional Airport (TIX), when the pilot declared an emergency.

Blatnik: 0BZ traffic’s now two o’clock and two miles westbound four-thousand 500 a Cirrus, let me know if you pick him up.

N400BZ: 0BZ is losing his engine – I need, I need the runway, 0BZ, declaring emergency.

Blatnik: 0BZ roger. Cleared visual approach, I’m just letting you know there’s traffic there. Cleared visual approach runway 2-7.

Blatnik continued to relay important information to the struggling pilot. Scheele coordinated a descent path with the controller in charge of the lower airspace, directing all aircraft away from the Cessna. Scheele also coordinated with the tower at TIX to ensure there would be no other traffic in the aircraft’s path.

In emergency situations, it is nearly impossible to predict how quickly an aircraft will descend. Blatnik and Scheele knew that quickly moving all aircraft out of the way was crucial to the safety of the pilot and everyone in the airspace. The pilot was beginning to sound frantic. Then he stopped responding for a few seconds.

Blatnik: N0BZ cleared to land any runway.

Blatnik: N0BZ cleared to land any runway, Space Coast Airport.

N400BZ: 0BZ.

As the aircraft rapidly descended, the pilot alerted Blatnik that he had lost an engine. Blatnik was able to give immediate clearance to the pilot in distress through his ability to quickly and effectively move nearby aircraft around without error or incident. Blatnik cleared the Cessna for visual approach to TIX and the aircraft landed safely, but then caught fire on the runway shortly after the pilot safely exited the aircraft.

Southern RVP Jim Marinitti:

Air traffic controllers work in an environment where we are expected to be right 100 percent of the time. There are no do-overs in a situation like this. Donald and Kenneth stepped up on the spot, during a busy session, without missing a beat. Without their fast actions, there is a possibility the pilot and his passengers would not have made it to the ground and out of the aircraft in time. Their actions represent the professionalism, teamwork, and bond that holds the National Airspace System together.

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

2015: Hugh McFarland, Houston TRACON (I90)

On November 16, 2014, longtime Houston TRACON NATCA member Hugh McFarland received a call from a distressed pilot who had become stuck on top of solid Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) weather. The pilot was only Visual Flight Rules (VFR) certified, and had encountered the weather conditions while en route from Kerrville, Texas, to David Wayne Hooks Airport, just north of Houston. After flying towards Houston for almost two hours, the pilot knew he needed more help.

After McFarland received the call from the pilot, he immediately began to make a plan to get the pilot safely on the ground. The weather the pilot was stuck on top of was almost 8,000 feet thick, and the conditions extended hundreds of miles around the Houston area. There was almost no chance the pilot could have flown his Cessna 172 to an airport with reported VFR conditions with the remaining fuel he had on board.

The decision was made to attempt a descent through the weather and have the pilot land at Houston Executive Airport (TME).

As a Beechcraft Baron aircraft owner and certified multi-engine instrument rated pilot himself, McFarland understood how critical it was that the pilot be able to land at TME. For 20 minutes, McFarland acted as the pilot’s navigation equipment and eyes through the weather. He prepared the pilot for the descent into TME, helped the pilot load up his GPS with the airport’s information, constantly reminded the pilot of his airspeed, bank angle in the turn, to stay calm, to breathe, to trim the aircraft, and to ensure the carburetor heat was on to prevent icing, among other things.

McFarland: N59G, you’re doing great, just keep the wings nice and level and airspeed about 85-90 knots, enrichen the mixture just a little bit more. Not all the way, but just a little bit.

McFarland: N59G, if you’re having to apply carburetor heat, go ahead and pull the carburetor heat knob out.

N4859G: Carburetor heat has been out, thank you.

McFarland: Roger.

McFarland: N59G, doing great, about another 500 feet to go, just continue southbound, heading 1-8-0, wings nice and level at 1-8-0, and just maintain 2,000 when you get there. About another 500 feet to go.

McFarland: N59G, when you’re ready, just make a standard-rate turn to the left, it’ll be just about 10 to 15 degrees of bank to the left, into a 0-9-0 heading, just due eastbound, just nice gradual turn, and use the turn coordinator and your attitude indicator to make just an easy turn to the left, about 15 degrees of bank.

McFarland also used landmarks to help assist the pilot in finding the airport. At 700 feet mean sea level, the pilot finally saw the ground. As the pilot descended lower, McFarland lost radar contact with the aircraft, but continued to provide the position of TME relative to the last known position of the aircraft until he heard the pilot had safely landed his aircraft.

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

Archie2015-Southwest from NATCA National Office on Vimeo.

2014: Nunzio DiMillo, Boston ATCT (BOS)

On September 27, 2013, around 7 p.m., JetBlue Captain T.R. Wood was piloting an Embraer 190 down Taxiway B at Boston Logan International Airport (BOS). At the same time, Nunzio DiMillo, a 23-year veteran controller, was watching out of the tower cab window as a Cirrus SR22 turned to line up for a landing on Runway 4L.

Oftentimes, pilots of smaller aircraft, like the Cirrus, will fly a dog-leg approach to Runway 4L. By lining up with the runway when they are over the numbers painted on the ground, they are usually able to avoid the turbulence and choppy air left behind by larger aircraft.

As the Cirrus pilot made the turn towards the airport, he apparently got confused. In the darkness, he struggled to find Runway 4L among the various lights on the airport, the lights of the city and the nearby harbor. Instead of lining up with the runway, the Cirrus pilot lined up with Taxiway B, and put his plane on a direct collision course with the JetBlue Embraer.

In the tower, DiMillo could tell something was wrong with the Cirrus’ approach. He quickly glanced up at the ASDE-X display and saw the Cirrus was lined up with Taxiway B. He immediately told the pilot to go around.

Nunzio: Six Bravo Juliet, go around. Six Bravo Juliet, go around, please. Go around.

N246BJ: Six Bravo Juliet is going around.

Nunzio: That was – you were lined up for a taxiway, Six Bravo Juliet.

About 30-feet off the ground, the Cirrus began to gain altitude, flying close enough over the Embraer that Captain Wood could hear the engine through all the noise proofing material that surrounds the cockpit. DiMillo, thinking the Cirrus pilot would probably be shaken up by the close call, kept him on the tower’s frequency as he executed the go-around. Meanwhile, the tower turned up the airport lights to help the pilot make a safe landing.

DiMillo himself had to remain calm as he continued to work the busy West Local position, a position that required him to talk to every landing and departing aircraft at Boston. In the hour that the event occurred, DiMillo spoke to 92 aircraft. His experience as a veteran controller helped him remain focused on the other aircraft under his watch.

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

A Video Tribute to the First 10 Years of President’s Award Winners

2013: Bill Sullivan, Tampa ATCT/TRACON (TPA)

On March 1, 2012, air traffic controller Bill Sullivan was directing a Piper Malibu [PA-46, N377HC] from Tampa Executive Airport to Tampa International Airport (TPA). But shortly after takeoff, the pilot declared an emergency due to flight control problems.

N377HC: Seven Hotel Charlie we got an emergency.

Sullivan: Seven Hotel Charlie state the nature of the emergency.

N377HC: I’m losing my controls.

Sullivan: Alright sir, do you need, do you want to land at Tampa International? Do you want to land back at Vandenburg? Or where do you want to go?

N377HC: You tell me, I’m trying to get my act together.

Realizing his best plan of action would be redirecting the pilot back to Tampa Executive, Sullivan began giving him the necessary coordinates to return to the airport. At the same time, he began handing off some of his workload so he could focus on the situation at hand and ensure that the service to the other flights he was responsible for would not be degraded.

The pilot was in clear distress. His breathing became rapid and he was unable to communicate his situation with Sullivan as he attempted to steer the aircraft in response to the turns being issued.

Sullivan continued directing the pilot until he finally saw the airport.

N377HC: How much further is this airport?

Sullivan: Seven Hotel Charlie, at your 11-10 o’clock now in about two and a half miles. It’s just on the other side of that interstate, sir…

Sullivan worked for several more minutes to assist the pilot in finding the airport, repeatedly pointing out its proximity to the interstate.

N377HC: Seven Hotel Charlie, got it! Finally!

Sullivan: Okay, sir. You can go ahead and resume navigation to the airport.

N377HC: Don’t leave me; this ain’t over.

Sullivan: No, sir. I’ll be right here.

Sullivan stayed with the pilot until he landed safely. When the pilot did land, he asked Sullivan for a favor – could he place an important phone call? The pilot asked if Sullivan could call his wife and let her know that he was no longer going to be at Tampa International and would need to be picked up at Tampa Executive.

Sometimes, being an air traffic controller is more than just directing air traffic. Sometimes you might need to direct someone’s wife to an airport.

BELOW: Watch the award presentation.

BELOW: Watch and listen to highlights from this save event.

Click here for a transcript of the highlights from this save event.

2012: Ken Greenwood, Seattle TRACON (S46), Josh Haviland (S46), and Ryan Herrick (S46)

“You know what? You just saved my life.”

Some of the most important words an air traffic controller could ever hear were spoken by the pilot of a Mooney, Jim Lawson, on Dec. 10, 2011, when it became clear that a harrowing turn of events – running out of fuel – would end safely at Renton (Wash.) Municipal Airport (RNT).

Had Seattle TRACON (S46) certified professional controller-in-training Ken Greenwood – an 18-year veteran of Boeing Field (BFI) with extensive knowledge of the area around Renton – not noticed quickly that the pilot was in fact turning away from RNT (toward BFI), the aircraft would have possibly hit the blast fence instead of clearing it.

Greenwood had less than 50 hours on position at S46, but he showed confidence as he worked with his instructor Ryan Herrick to direct the pilot’s descent from above a cloud layer. The pilot had called in VFR conditions above an IFR layer, looking for a VFR hole to get down and land at Auburn Municipal Airport. But Auburn would not remain his destination for very long.

“We got a PIREP (pilot report) from another sector about a VFR hole 25 miles southeast of Sea-Tac,” Greenwood said. “I gave a VFR vector toward Thun Field (PLU) and gave weather for Thun and TCM (Tacoma-McChord Field).” At that point, trainee Josh Haviland plugged in next to Greenwood. Haviland had previously owned a pilot training school and is a flight instructor.

The pilot reported that he was already out of gas in one tank and almost empty in the other and was still on top of the cloud layer at 7,700 feet. Greenwood gave him a vector toward Auburn airport and a decent clearance to 4,000 feet.

“The pilot was very busy or distracted, possibly trying to set up his GPS,” he said. “He was not answering all our transmissions and he was not flying the headings we issued very well.”

At this time, several controllers were coordinating with the SEA, BFI, and RNT towers. All departures had been stopped and VFR aircraft were being sent out of the VFR pattern at RNT. Herrick called SEA local assist to ask if anyone could see any breaks in the overcast.

At 3,200 feet, the pilot reported he had ran out of fuel and that he was still in the clouds. Haviland suggested to Greenwood that he give the pilot the best glide speed and level flight. At 2,200 feet, the aircraft reached VFR conditions four miles south of RNT.

But at 1,600 feet, the pilot saw BFI, which was more than six miles to the northwest. Greenwood saw him start to turn toward BFI but then acted quickly and decisively to get him to turn back toward RNT. He got the airport in sight at 1,100 feet. A safe landing ensued.

Pilot: You know what? You just saved my life.

Greenwood: Anytime, sir.

Anytime, indeed.

2011: Derek Bittman, Atlanta ARTCC (ZTL)

On Jan. 16, 2010, certified professional controller Derek Bittman stumbled across a particular situation that could have easily changed forever the life he had come to know so well.

Bittman was working the Dallas sector at Atlanta Center that day, the busiest and most complex sector in the world, when he was handed over a pilot with navigation equipment mal- functions. This pilot, planning to end his trip in the Atlanta terminal area, had already missed two approaches at the destination due to low ceilings and fog, and furthermore, was low on fuel. After discussing various choices, the pilot opted to proceed to Rome (RMG) for a last attempt, a fairly busy general aviation airport 60 miles northwest of Atlanta.

Bittman: If you can’t make this approach at Rome do you want to go, try and go somewhere else? Do you have a plan B?

N3011N: This was plan B, one-one november.

Confirming Bittman’s fears, the pilot declared a few minutes later that he was still not able to find the airport. With rapidly diminishing options and only 45 minutes of fuel remaining, N3011N was now in a very desperate situation.

After advising that his only offer for the aircraft at this point would be another attempt of the ILS into RMG, Bittman learned that the pilot was not only having trouble with his glide slope on the VOR but his lateral CDI, as well. In receiving this information, Bittman declared an emergency on behalf of the pilot. Providing vectors back to the RMG VOR, he informed the pilot of the area’s numerous highways should the escalating situation resort to immediate landing.

With the VOR the pilot was using to find the airport now malfunctioning, Bittman was forced to use his last resort. Having already split off the sector in order to provide sole attention to the aircraft, he began application of his knowledge from past Marine Corps experience to help this pilot find the airport. He provided precision vectors, similar to an ASR approach, to the aircraft while using the approach plate to give vertical guidance – a tactic not commonly used by the enroute center due to its unreliable radar data and the absence of minimum vectoring altitudes.

Bittman: November one-one november, uh, make sure you understand sir, the calls that I’m giving you are suggestive in nature sir. I do not have a glide slope or a localizer depicted on the scope.

Bittman: Increase the rate of descent… appears you’re left of course and going farther left. Turn five degrees right.

Bittman: November one-one november, radar contact lost, two and a half miles south of the Rome Airport. Last track I had on you had you on course into Rome Airport.

Due to the quick actions by this educated controller, the pilot was able to make visual contact with the runway right before the touchdown point. As it happens, he ran out of gas while taxiing to the ramp, confirming the fact that Bittman’s efforts saved his life.

Bittman used his experience and his skill to help this pilot in his efforts to reach the ground, remarkable qualities both honorable and extraordinary. Bittman made a truly committed controller’s decision – the decision to do whatever it took to save a life.

2010: Jessica Anaya, Lisa Grimm, Nathan Henkels, Miami Center; Dan Favio, Brian Norton, Carey Meadows, Fort Myers Tower/TRACON

“I’ve gotta’ declare an emergency. My pilot’s…unconscious. I need help up here.”

These stirring words hung heavy in the air as Doug White (pictured above with his family), passenger of the King Air aircraft, reached out for help – help from anyone that could provide it on this busy Easter Sunday.

“My pilot’s deceased… I need help.”

While his wife and two daughters looked on in shock, White took over the cockpit as various Miami controllers began to lighten the load of Nathan Henkels and Lisa Grimm who immediately made moves to assist the troubled passenger.

Though a private pilot, White had never flown a larger, two-engine King Air and was now in a life-threatening situation as the plane hit 5,000 feet and continued climbing.

AUDIO: Miami Center Members Work With Doug White. Click here.

As Jessica Anaya stepped in to coordinate the rerouting of all aircraft in this high traffic area of Southern Florida, Grimm worked to calmly explain the specifics of the aircraft to White as he frantically sought to turn off the autopilot.

“Number five delta whiskey, disengage the autopilot. We’re gonna have you hand fly the plane,” she instructed. “Hold the yoke level and disengage the autopilot.”

“Alright, I disengaged it,” stated White, surprisingly composed as he was forced to take action in order to stop the climb. “I’m flyin’ the airplane by hand.” And, in his typical light-hearted demeanor that seems to find humor in any situation, followed it up with a request for Grimm to find the longest, widest runway she could.

“You doin’ alright there descending?” Grimm asked a few minutes later, as she did repeatedly throughout the event. “I felt as long as he had some reassurance, he had enough skills to successfully manipulate the controls and bring the plane down,” recalls Grimm of her actions that day.

“Oh, we’re havin’ a hoot, niner delta whiskey,” White responded in his thick southern drawl.

He lay in the hands of a team that had quickly formed an assembly line formation in order to successfully alternate between transferring control on the radio channel, advising the passenger, and issuing control instructions to other aircraft. Through the pilot experience so patiently displayed by Grimm and the hard work of Henkels and Anaya, White was able to get the plane in the appropriate position to steer towards Ft. Myers Airport where Dan Favio, Brian Norton, and Carey Meadows were waiting to take over.

AUDIO: Fort Myers Members Work With Doug White. Click here.

It was at this point that Favio called up good friend and veteran pilot Kari Sorenson of Danbury, Conn., for help in talking White down. Also a flight instructor, Sorenson was able to relay important details via cell phone regarding the positions of controls, switches, and how to configure the King Air for landing. Favio and Norton, set up on a single scope and a separated frequency to allow for complete focus, received the instructions from Sorenson which they carefully echoed to White. With a successful touchdown finally completed, the two handed the aircraft off to Meadows at ground control where he proceeded to assist White with shutdown instructions.

With one unfortunate and unpreventable death, came the incredible saving of four others thanks to those who worked the skies that Easter Sunday. The teamwork was unmistakable as the experience and calm composure of the controllers in Miami joined forces with the quick-thinking skills of the Fort Myers team. Enhanced by the unforgettable courage displayed by Doug White through these adverse circumstances, the ATC system worked together from tower to center, from pilot to passenger, to bring a successful end to this unexpected and traumatic event that could have easily gone from bad to worse.

“The husbands and the wives of air traffic controllers have no idea what their spouses do for a living,” said White after the fact. “When something good happens, air traffic controllers don’t get the high-fives and the ‘attaboys.’ I’m going to give them the ‘attaboy.’”

View transcript of event highlights.

BELOW: Watch the presentation of this event, including the ATC audio replay, during the Southern Region portion of the 2010 Archie League Medal of Safety Awards banquet on March 22, 2010, at Communicating For Safety 2010 in Orlando, Fla.

View the radar replay while listening to the full ATC audio (below).

Joining the controllers on stage for the President’s Award with NATCA President Paul Rinaldi, Executive Vice President Trish Gilbert, and Southern Regional Vice President Victor Santore was Doug White. In this video below, White delivers emotional remarks in a riveting ceremony that captured one of the most dramatic events in the history of the Archie League Medal of Safety Awards, which NATCA began in 2005.

2009: John Charlton, Lake Charles Tower/TRACON

John Charlton displays dedication and professionalism continuously as an air traffic controller at LCH, and on Sept. 23, 2008, he once again went above and beyond to ensure a safe end result to a situation that could have easily ended in tragedy.

On this specific day, it was Charlton’s patience that saved the day. He was working local control when a Delta State University student pilot came over frequency requesting clearance. After clearing the Cessna 172 to land on Runway 15, Charlton watched as it made two unsuccessful attempts.

Charlton could sense the student was becoming flustered and, knowing what nerves could do in a situation such as this, he took it upon himself to provide some extra attention to the aircraft. After offering advice for a third attempt that proved unsuccessful, he alerted crash and rescue as a precaution for this risky predicament that had so quickly developed.

He instructed the pilot to do as he said without responding back. This would allow her to focus on his words, and his words alone. He spent the rest of the flight talking her through cross wind correction, keeping proper airspeed and finally through the instructions for cutting power towards descent. When the aircraft started to settle, he instructed the pilot to add pitch and, after a total of four unsuccessful attempts, the aircraft finally touched down successfully. Before ending the assist, Charlton made sure that the pilot had applied her brakes and taxied clear of the runway in order to not only ensure her safety, but the safety of those around her.

“[John’s] actions speak highly for the amount of dedication that he showed on this day and every day that he reports to work at FAA LCH ATC,” describes Lake Charles Regional Airport Director of Public Safety, Chad Primeaux, who has more than 18 years of experience in the airport public safety business. “If it had not been for Charlton’s professionalism and dedication to the job at hand, the end result would have been a totally different event than the one that occurred.”

Charlton demonstrated these significant qualities at such an imperative time, remaining calm and alert as he continued to work other aircraft and ground vehicles. In addition, he showed remarkable tolerance for the young pilot, one who was physically shaking from the traumatic experience she had just endured.

“Through the years, I have heard and witnessed a number of emergency situations involving aircraft,” wrote airport Executive Director Heath Allen in a letter to the Federal Aviation Administration. “I can’t say that I have ever observed such a devoted, extraordinary effort that Mr. Charlton gave to ensure that the young pilot landed safely and walked away unharmed.”

Below: Listen to highlights from this save.

2008: Patrick Eberhart, Detroit TRACON

“This was without a doubt, an actual emergency. Our lives were in his hands.”

These were the words written by Ryun Black, the pilot of a Beech Bonanza that experienced an emergency on the night of Jan. 3, 2007, and was safely directed towards Pontiac (Mich.) Airport by Detroit TRACON controller Patrick Eberhart. “I want this controller to know that I will never forget what he did for us that night,” wrote Black.

The incident began when Eberhart noticed that the BE35 was off course on its initial approach into PTK. Eberhart coordinated with the Pontiac Tower to have the aircraft abandon the approach and he would vector him back around for another try.

Just as Black abandoned the approach, he radioed, “We’re critically low on fuel.” Eberhart heard the emergency call and immediately came on the frequency. Eberhart then confirmed with Black that he was declaring an emergency, and set about to vector Black towards PTK.

Black also informed Eberhart that his instruments were not working properly and that he would need vectors to the airport.

Eberhart slowly began to clear his radio frequency so he could focus all of his attention on the aircraft in distress.

Eberhart informed Black he would be issuing vectors to a surveillance radar approach to PTK, a procedure controllers in the Detroit TRACON have not used in over 10 years. But due to his experience as a controller and knowledge of the area, Eberhart felt he could safely vector the aircraft towards the runway.

As he was issuing the vectors, Eberhart noticed the pilot was not properly flying the assigned headings, which he attributed to the instrument outage on the aircraft. Because of this, Eberhart began to issue no-gyro vectors to the final, another skill that has not been used in the TRACON for over 10 years. In no-gyro vectors, the controller essentially tells the pilot when to start and stop a turn.

“[The controller] made it very simple by giving us start turn, stop turn vectors and eventually gave us an altitude that got us below the clouds with the runway in front of us – brightly lit,” Black reported in his letter.

Thirteen minutes after the initial emergency call was issued, Black was able to successfully land the aircraft at PTK.

“I am grateful for (Eberhart’s) swift action,” wrote Black. “He could tell from my voice that it was of vital importance to be expeditious and accurate.”

“Pat relied on a procedure that we haven’t used in over 10 years to get the aircraft on the ground,” stated Detroit TRACON NATCA Facility Representative Jeff Blow. “This is something only an experienced controller would know how to do.”

By relying on his experience and knowledge of the area, Eberhart was able to safely vector an aircraft critically low on fuel to a safe, uneventful landing at PTK. Just another day at the office.

2007: Chris Thigpen, Kansas City Center

To a distressed pilot, the calm reassurance of an air traffic controller’s voice is their lifeline to safety. Even experienced pilots encounter trouble and must rely on controllers to guide them home. On Oct. 10, 2006, Charles Schultz, piloting his Beech Bonanza (N1801V), found himself in this situation and turned to Kansas City Center (ZKC) controller Chris Thigpen for guidance.

Schultz was headed from Scott City, Kan. (TQK), to Hays, Kan. (HYS), when another ZKC controller, John Bloomingdale, noticed the Bonanza making erratic turns. He radioed Schultz to ask his heading and when it did not match what the radar indicated, Bloomingdale assigned Schultz a different heading. But Bloomingdale knew the Bonanza was in trouble.

Bloomingdale declared an emergency and turned to Thigpen, who was working the next position, for help. Bloomingdale knew that Thigpen, a private pilot, would be able to assist Schultz. This decision proved correct, as Thigpen would spend the next 30 minutes guiding the Bonanza to safety.

Thigpen sat down next to Bloomingdale and, according to ZKC Facility Representative Scott Hanley, “it was as if Thigy was a paramedic walking up to a train wreck. He was assessing everything, listening to John [Bloomingdale], watching N1801V, listening to the supervisor, and checking weather at Great Bend, Kan. (GBD), HYS, and Russell, Kan. (RSL) all in a matter of seconds. Then Thigy took charge.”

Thigpen cleared all other aircraft from the frequency and focused on the Bonanza. He realized Schultz was suffering from spatial disorientation and knew that he needed to level his wings, watch the artificial horizon, and keep his eyes inside the aircraft. After 10 minutes of working with Schultz to level the plane and stay on a correct heading, Thigpen took the extra step of establishing a personal relationship with the pilot.

Thigpen: N1801V, what’s your name?

N1801V: Charles Schultz.

Thigpen: Hey Charles, my name is Chris. We are going to point you out toward Great Bend, Kan.

N1801V: That’s great.

From that point on, Thigpen referred to N1801V as Charles. Thigpen even asked him if there was anyone he could contact for him to let them know he would be landing in Great Bend instead of Hays.

With Schultz experiencing spatial disorientation, his instruments were useless. Thigpen took away his instruments, gave him no-gyro vectors all the way and kept repeating for Schultz to keep his eyes inside the plane. As the Bonanza approached Great Bend, Thigpen had a fellow controller radio another aircraft in the area to turn the lights on at Great Bend, so Schultz would be able to locate the airport. “Thigy essentially flew the airplane, completed the checklists and ensured the airport was lit for Charles,” added Hanley.

Finally, after thirty minutes of vectoring, the airport was in sight. Schultz landed the plane safely and then called ZKC to personally thank Thigpen. “I really needed you tonight and you really came through,” he told Thigpen.

Because of Thigpen’s calm and reassuring voice, Charles Schultz was able to make it home safely that night.

Below: Highlights from this event.

2006: Jesse Fisher, Miami Tower

The scenario had all the makings of a disaster. It was dark. Traffic volume was heavy and complex. The local control positions inside Miami Tower were combined. The radio frequency was congested. The weather was marginal. Visibility was poor. And the airport’s Airport Movement Area Safety System was in limited mode, meaning it was not providing controllers with aural or visual alarms to signal potential runway incidents.

Controllers in the tower were using Runways 26 Right (26R) and 27 for arrivals, using staggered instrument approaches, and departing on Runways 26 Left (26L) and 27. Rain obscured both the movement area and final approach courses. Veteran tower Controller Jesse Fisher was working the Local Control North (LCN) position, combined with the Local Control South position.

A Lockheed L329 Jetstar was on approach to Runway 26R. The pilot checked in with Fisher on the LCN frequency and Fisher cleared him to land on Runway 26R. The pilot acknowledged the clearance and subsequently reported that the runway was in sight.

Meanwhile. American Airlines Flight 2104, a Boeing 737, was taxied into position and holding on Runway 26L, awaiting takeoff clearance, due to in-trail separation with traffic departing Runway 27, and traffic crossing the runway. Additionally, American Airlines Flight 1917, a Boeing 757, which had just arrived on Runway 26R, was instructed to cross Runway 26L and was advised that traffic (American 2104) was holding in position.

As Fisher scanned the movement area and the final approach courses, he saw the Jetstar on short final approach, at approximately 200 feet off the ground, lined up with the wrong runway – 26L instead of 26R – with American 2104 holding in position and American 1917 crossing the runway downfield.

Fisher immediately instructed the Jetstar to execute a go-around and the pilot complied. He appeared to overfly American 2104 by approximately 100 feet and American 1917 by about 400 feet.

Upon hearing and seeing what was happening, the pilot of American 1917 keyed the radio microphone and uttered an expletive. Shortly thereafter, an unidentified aircraft waiting in line for departure off Runway 26L keyed the mike and said, “Good job, tower!” Another unidentified aircraft waiting in line for departure then transmitted, “Nice save, tower!” When American 2104 was cleared for takeoff, the pilot’s reply was, “Hey, a huge thanks from us.”

Fisher’s quick instruction to the Jetstar pilot was even more important considering that Runway 26L has no displaced threshold, meaning the distance between where American 2104 was holding in position and the point where the Jetstar would have touched down is indiscernible.

“One of the key elements that make Jesse’s actions so outstanding is the fact that Runway 26R and 26L are in such close proximity, with only 800 feet between the center lines,” Miami Tower NATCA Facility Representative Jim Marinitti said.

“Additionally, when you factor in that the tower is located on the opposite side of the airport from the west final approach courses – over two miles away – and that the arrival aircraft appeared to be on the correct final until very close to the airport, it makes it that much more remarkable that Jesse was able to identify this pilot error and take action in time to prevent a catastrophe at night with limited visibility.”

Fisher has worked at Miami Tower since 1991. Adds Marinitti: “It is not a cliché to say that an untold number of passengers arrived home safely on this day due to, but completely unaware of, Jesse’s outstanding situational awareness and heroics on the job. Jesse’s valiant performance truly exemplifies what makes our aviation system the safest in – and the envy of – the world.”

Andy Cantwell, Southern Region Vice President:

“I have personally known Jesse for 15 years and have always considered him to be the consummate professional. On March 18, Jesse once again demonstrated his professionalism and expertise. His attention to detail and quick reactions prevented a foreign general aviation aircraft from landing on a runway that was occupied by a B737 awaiting a takeoff clearance and a B757 crossing the runway downfield. On that night, Jesse was working combined Local Control positions during a period of heavy traffic and marginal weather conditions. The centerlines of Runways 26 left and right are separated by only 800 feet. The runway threshold is approximately two miles away from the tower and it is difficult to determine if arriving aircraft are lined up for the correct runway during daylight and good weather conditions. Fortunately, Jesse did notice that the arriving aircraft was lined up with the wrong runway and quickly issued instructions that prevented a major disaster. In addition to darkness and poor weather conditions, the Airport Movement Area Safety System (AMASS), was operating in limited mode and did not provide any aural or visual alarms of the impending disaster Having worked at MIA for over 24 years, I am intimately aware of just how remarkable Jesse’s actions were on that night. The fact that several pilots commented on the situation means they were also aware that Jesse averted a deadly situation. Jesse believes he was simply doing his job. He did his job perfectly on that night.”

2005: Ken Hopf, Boston TRACON

It was the call no controller ever wants to receive. A panic-stricken voice from aboard an aircraft in trouble crackles over the frequency. The pilot is unconscious. And neither of the two passengers holds a pilot’s license.

But that was precisely the situation presented to Hopf as he worked the flight data Manchester position, which is also responsible for issuing instrument flight rules clearances and releases off of uncontrolled satellite airports. Just after 4 p.m., he received a call on the clearance delivery frequency from Jennifer Truman, aboard a single engine 1988 Piper Malibu that had just taken off from Laconia Airport in central New Hampshire.

Truman requested immediate assistance. The pilot, her father William, was incapacitated. Her mother, Diana, was tending to him.

Hopf located the aircraft on his radar scope and then put his 22 years of controller experience – along with his knowledge as a Certified Flight Instructor – to work.

“I tried to calm her down and determine her ability to fly the plane. She said that she had flown a Piper Cherokee before, but had never flown the Malibu,” Hopf stated. “I assigned her some headings to fly. Her ability to do so and maintain altitude demonstrated to me as a flight instructor she had the ability to fly the plane. She just needed help landing it.”

Hopf’s colleague at Boston TRACON, Bob Romano, said Hopf’s calm voice had an immediate effect on Truman and she was better able to focus on piloting the complex aircraft despite the traumatic circumstances. Hopf talked with Truman about the best place to land and she decided it should be Laconia because of her familiarity with the area and the runway.

Hopf spent the next 15 minutes working with Truman to prepare the plane for landing.

“Getting the landing gear down and speed control were the most important things,” he remarked. “She was very confident in her ability to fly headings and maintain altitude. I had to try to keep things simple; I didn’t want to get too technical and overwhelm her.”

“Then,” Hopf added, “her mother became incapacitated. I no longer felt I had the time to work with her on speed control. I just needed to get her to the airport. I asked her to open a vent or window because it sounded like carbon monoxide poisoning. I turned the plane on a base leg and started her descent explaining the use of the throttle to slow the plane down. We also talked about what to do when the plane lands; to use the brakes and stop the engine. She slowed the plane up and descended and leveled off without any problems. I felt very confident at this point that if we got her lined up with the runway, that she could land the plane.”

Truman then reported the airport within sight. “I was trying to listen to her voice to see if I detected any signs of it becoming slow,” Hopf commented. “I asked her to slow the plane some more and line it up with the runway.”

When Truman was on short final, Hopf asked her to tell him when she was on the ground. A few moments later, that transmission arrived as music to Hopf’s ears.

“At that point, she broke down. I mean, I could tell her emotions just totally took over,” Hopf said. On the frequency, the relief in Truman’s voice was palpable: “Thank you very much. There’s the fire department. Thank you very much.”

Concluded Hopf: “You think back of all the things that could have went wrong. I mean, this was a case where everything went right. Everything just was perfect.”

Mike Blake

New England Regional Vice President

When you meet Ken Hopf, you immediately understand why he is not only a deserving, but likable honoree in this, the first Archie League awards program. A calming nature, engaging personality and infectious sense of humor help to ease co-workers and pilots alike. I remember first meeting Ken 21 years ago at Boston Center. He made the impossible happen for me, even back then, when he could make me laugh as the lowliest developmental, encouraging me to succeed. Heck, I even think I looked forward to coming to work.

Ken is an Air Force veteran, having worked as a crew chief on F-4 Phantoms at Nellis AFB in Nevada. He was initially hired by the Federal Aviation Administration as an Airways Facilities technician and worked at Providence, R.I., for several years. Ken then transferred into air traffic, working at Boston Center, Groton Tower, Worcester Tower, Manchester Tower and now at Boston Consolidated TRACON.

Ken’s love for aviation is well-known. As a private pilot, flight instructor and air traffic controller, he has shared his love with many others. He has exceptional knowledge on aircraft systems and airmanship. Ken is deeply involved in his flying club, and, in fact, maintains the club’s aircraft.

Ken and his wife, Kathy, live in Bow, N.H., where they raised two grown daughters, Annie and Mary, in a house that Ken built. He is an avid snowboarder as well. One of my favorite things that I heard about was that Ken’s personable nature has earned him the nickname “Mr. Wonderful” by Kathy’s co-workers!

Listen to this flight assist below: