2020 – Winners of the 16th Annual Archie League Medal of Safety Awards:

Alaskan Region: Matthew Freidel, Anchorage Center (ZAN), and John Newcomb, Anchorage TRACON (A11)

The weather conditions in Alaska are often poor, but they’re highly changeable. This can lead to situations where a pilot can encounter difficulty, especially if they’re not able to fly in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC). Alaskan Region air traffic controllers are keenly aware of this each time they plug in for a shift.

“I’ve seen situations where a pilot gets IMC for 30 seconds, they call up needing help, and they’re out of it in 15 to 20 seconds,” said Anchorage TRACON (A11) member John Newcomb, a second-generation controller who was a member of the 235th Air National Guard ATC Squadron before starting his Federal Aviation Administration career in 2014. “Other times, like this situation where it’s prolonged, you’re getting PIREPs from other airplanes and ground facilities, or from other pilots who are climbing out, descending in, or in level flight. But it’s not uncommon up here.”

On this particular Sunday morning, the VFR-rated pilot of a Cessna 172, N758XS, encountered IMC after departing Soldotna Airport (SXQ), headed to Birchwood Airport (BCV). Worse, the initial transmissions from the aircraft were garbled. Newcomb and his colleague from Anchorage Center (ZAN), Matthew Freidel, worked with assistance from their respective facility teams to aid the pilot, including vectors and recommended altitudes. Freidel earlier this month marked his nine-year anniversary in the FAA, all at ZAN. His love of aviation started at age 17 when he learned to fly gliders. He studied first commercial aviation and then air traffic control at the University of North Dakota.

In an area as vast as Alaska, controllers have lots of frequencies, but lots of limitations on their frequencies, such as line of sight. Mountains are everywhere.

“Garbled transmissions are common,” Freidel said. “But something about it felt strange and just compelled me to follow up on the transmission. I couldn’t really understand what was going on for a couple of transmissions.”

Soon, however, Freidel received help in the form of a climbing Peninsula Airways flight. The pilot could hear the broadcast on their end. It served to clarify for Freidel that it was indeed someone he should be talking to as opposed to a bleed-over from another frequency.

“At that point, it changed the whole dynamic of, ‘OK, what am I going to do?’ to ‘What do I need to figure out here?’” Freidel said.

As soon as N758XS appeared on radar, Freidel could finally see what was happening. “It looked like they were precariously heading toward mountainous terrain on the northeastern Kenai Peninsula,” he said. Freidel had a keen awareness of that airspace, having flown around it and been in Alaska for a while, so he knew the other direction was flat with short spruce trees comprising the terrain. Therefore, the impulse was to get the pilot of N758XS turned in that safer direction.

“I think the pilot did a fantastic job of flying her airplane in a moment of distress because she took the squawk code, she took all of the instructions, she kept the aircraft’s wings level, she climbed when I asked her to climb,” Freidel said.

Once the pilot was pointed in the right direction, the remainder of the event was fairly straightforward, both Freidel and Newcomb said.

Newcomb would soon have responsibility for the aircraft as it entered his airspace. He was plugged in, working to get a briefing started for the south radar position. Fellow A11 member Adam Herndon took the handoff first as Newcomb stood behind him and they discussed the situation. Herndon said he would give Newcomb the sector while he coordinated with ANC, Merrill Field (MRI), and Lake Hood Airport (LHD) to determine weather and visibility conditions.

“It was a team effort right there, and 8 XS did a great job, with wings level, climbed, did not descend,” said Newcomb. He advised the pilot she was close to ANC and “don’t worry about the Class Charlie. Just continue, and flight conditions should improve once you hit the shoreline.” Everything was coordinated by A11 so the pilot did not have to switch over to ANC.

ZAN member Chris Weldy said Freidel did a great job quickly diagnosing a pilot in distress, with initially barely readable transmissions. That set the story on a course to have a safe ending.

Watch the awards presentation:

Listen and watch highlights of this flight assist:

Podcast below: Hear Freidel and Newcomb tell their story, and discuss their efforts to guide the Cessna pilot away from trouble to a safe landing, in this episode of the NATCA Podcast.

Central Region: Sarah Owens, Kansas City Center (ZKC)

At Kansas City Center (ZKC), air traffic controllers on position have a list available to them of fellow controllers at work who are also pilots. If needed, those controllers can be brought to the area to assist a pilot in distress, including things like reviewing emergency checklists. Flying an instrument approach in a small, single-engine aircraft is a very high workload environment, and controllers who are also pilots understand this best.

“The pilot needs to be constantly scanning their instruments and providing continuous corrective inputs to the aircraft controls to ensure that the aircraft remains on course,” said ZKC member Sarah Owens.

The pilot of a Piper PA-28, flying in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) in February 2020 and encountering some instrument failures, needed help. The controller on the other end of the microphone happened to be the perfect person for the situation: Owens. Now in her 20th year at ZKC, Owens (pictured below) has been flying for the last 14 years. She flies jets, has worked for charter companies and flown around the country, and is also a flight instructor. She’s an Air Force veteran, a member of NATCA’s Air Safety Investigations Committee, and has represented NATCA at numerous pilot-controller meetings including at the annual Experimental Aircraft Association AirVenture Oshkosh.

Owens had just taken over working sectors 44/48 in the Trails Area. The pilot was attempting to intercept the Runway 31 localizer and land at Topeka Regional Airport (FOE) in Kansas but missed the approach and was being vectored back around for another instrument landing system (ILS) attempt. The pilot was instructed to maintain 3,000 feet until he was established on the localizer, which is basically the final approach course. Owens noticed the pilot made a very large turn to the left, approximately 40-50 degrees. This put the aircraft in a position where he would not be able to receive the localizer signal to intercept the final approach course. Worse, he was descending. Owens issued him a low altitude alert. She instructed him to climb and maintain 3,000 feet. He was at 2,000 feet. Owens worked with the pilot, advising to keep the wings level and climb. Her initial thought was that he was spatially disoriented, or experiencing a mechanical malfunction, or a combination of both. She soon found out the details.

“Being 1,000 feet below your assigned altitude is a dangerous situation when you are that close to the ground,” Owens said. “When he was at 2,000 ft. MSL (Mean Sea Level), that is approximately 800-900 feet AGL (Above Ground Level). If you look at the ILS31 approach chart at FOE, there are numerous towers that are depicted on the chart. Some of these towers are over 500 feet tall. If he kept descending, his altitude would put him in a dangerous proximity to these towers, which he would be unable to see while in the clouds.”

Vision is one of our most dominant senses. When you are flying in IMC or at night without a visible horizon, it’s very easy to become spatially disoriented. Statistics show that approximately 10% of general aviation accidents are due to spatial disorientation, and 90% of those are fatal. “At this point, I did not know why the aircraft was not on course,” Owens said. “It is extremely easy to become distracted by a malfunctioning instrument; you divert your attention to this new problem that needs to be solved, and now you become spatially disoriented.”

“The pilot informed me that he was having a Static System Failure,” Owens continued. “There are two components to the Pitot/Static System, the Pitot Tube and the Static Ports. In the most basic explanation, the Pitot Tube receives air that provides airspeed information, and the Static Ports measure air pressure, which provides altitude and vertical speed information. Depending on where the blockage was in the system, it would cause failures to different instruments (airspeed indicator, vertical speed indicator, altimeter). With a Static Port blocked, he was most likely receiving erroneous information from his vertical speed indicator and his altimeter. The vertical speed indicator displays the rate that the aircraft is climbing or descending. The altimeter displays your altitude. Both of these instruments are essential when flying an instrument approach.

“I knew that the weather conditions were better to the east of Kansas City. If the pilot could get back above the clouds, he would regain his ‘vision,’ and would no longer be relying on the instruments that were failed for navigation. Once he is out of the clouds, the emergency is basically resolved.”

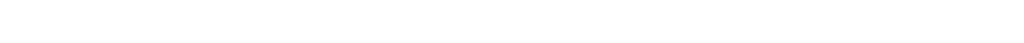

The pilot told Owens he was picking up icing. She checked his fuel status and helped him find VFR conditions. He was then able to get the aircraft under control. That’s when they found Lawrence Smith Memorial Airport (LRY) in Harrisonville, Mo., which is 40 miles south southeast of downtown Kansas City and approximately 80 miles east southeast of Topeka.

“My main concern was his proximity to the ground, and obstructions,” Owens said. “I needed to get him back into conditions where he could see visually and not need the failing instruments to navigate. Once I observed that the aircraft’s pitch changed from descending to climbing, I knew then that the severity of the situation was decreasing. The pilot quickly climbed on top of the clouds and was able to navigate visually.”

It was about a 10-15 minute flight for the pilot and all that was left to do for the controllers was coordination, and making sure the aircraft continued flying safely.

Owens is the 11th ZKC member to win the Central Region Archie League Medal of Safety Award, joining Andrew Crabtree (2019), Josh Giles (2018), Andrew Cullen and Jeffrey R. Volski (2017), Liam Keeney and Brett Rolofson (2016), Andrew Smith and Joseph Moylan (2014), Todd Mariani (2012), and Chris Thigpen (2007).

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Central Region: Dean Hittner, Hunter Rubin, and James Smart, Wichita ATCT (ICT)

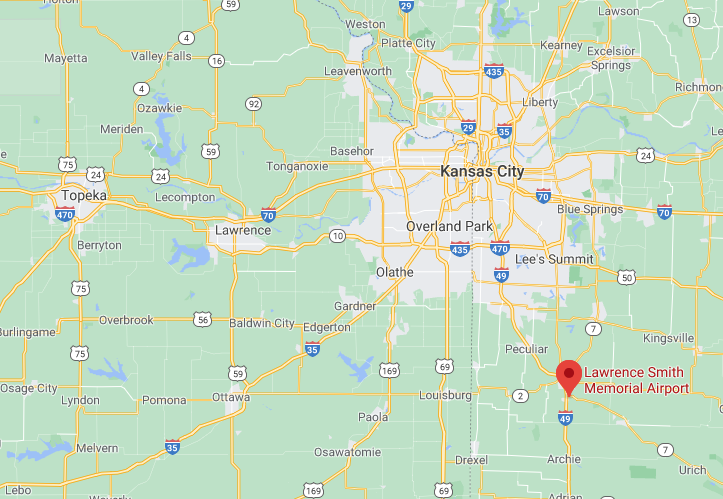

In 1929, the Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce dubbed Wichita, Kan., the “Air Capital of the World.” Nearly a century later, with a world-leading total of aircraft manufactured, it could be argued that Wichita’s busy-and-getting-busier airspace above six airports and McConnell Air Force Base makes it a strong candidate to keep that title. That presents clear situational awareness responsibilities and unique challenges for the air traffic controllers at Wichita ATCT (ICT).

ICT sits on the western edge of the city. On the eastern side, there are three airports lined up in a row, north to south, including two — Colonel James Jabara Airport (AAO) and Beech Factory Airport (BEC) — that are only three miles from each other with similar runway layouts. McConnell AFB is only six miles south of BEC. ICT member Hunter Rubin (pictured above, top right) grew up loving aviation as the son of retired controller Barry Rubin, who worked at Fairbanks ATCT (FAI), Albuquerque ATCT (ABQ), and Albuquerque Center (ZAB). Hunter said he found the perfect facility for him in ICT where each day brings the steady rhythm of traffic as volume rises and fills each radar scope.

“Once you start seeing all the VFR targets tagging up, and traffic picking up here and there, we’re like, ‘OK, here they come,’” said Rubin. He notes that they often open up a second and third radar position because “that east side of Jabara, Beech, and McConnell is just so congested. Everybody watches that area a little more carefully.”

AAO was the site of one of the most notable examples of a wrong airport landing in modern aviation history. In 2013, the crew of a massive Boeing 747 Dreamlifter cargo airplane, arriving from the northeast, mistakenly landed at AAO, a non-towered airport, instead of at McConnell AFB which sat just nine miles away in the distance. That was three years before Rubin started his career at ICT, but every controller at the facility knows situational awareness is critical. The rule is, “if you see something, say something.”

Midday on a Wednesday in January last year, Rubin saw something and immediately acted to prevent a wrong airport landing. Toward the end of his shift, Rubin was working the radar data position issuing clearances to aircraft at AAO and BEC. Fellow ICT member Dean Hittner was providing on-the-job training to James Smart on the radar east position. A Cessna Citation 680, coming in from the southeast, was being vectored for a visual approach into AAO. It was a clear VFR day and the Citation pilot called the airport in sight from 20-30 miles away.

The Citation was instructed to descend to 3,000 feet and the expectation was that the pilot would follow the established procedure into AAO of crossing the airport at midfield and entering the downwind on the west side. The pilot requested to cancel IFR, which is common and encouraged so that the one-in, one-out operations with AAO and BEC can proceed efficiently. The pilot also requested to switch to the Common Traffic Advisory Frequency (CTAF). Smart approved the request and instructed the pilot to remain clear of the Class Delta airspace at BEC. The tower at BEC called and requested takeoff clearance for Gulf Coast Aviation Flight 94 off runway 1, which Smart approved.

Rubin then saw the data tag on the Citation disappear. Suddenly, the aircraft was rapidly descending to 2,000 feet, which was not normal to him. Worse, the aircraft was now deviating off course and turning to the left, pointing to BEC.

“It just didn’t seem right. It wasn’t feeling right,” Rubin said. “I just think he had the wrong airport at the wrong point. I wasn’t expecting that target to disappear the way it did. That caught my attention.”

Rubin quickly alerted Smart and Hittner and they called BEC to advise them. The controller at BEC canceled the Gulf Coast Aviation flight’s takeoff clearance and broadcast on the CTAF for the Citation to go-around. Rubin saw the Citation’s data tag come back up at 2,300 feet as he passed over BEC. The quick action taken by Rubin, Smart, and Hittner averted both a wrong airport landing and a very dangerous situation of the Gulf Coast Aviation flight taking off into the path of the Citation. There is no taxiway at BEC other than a midfield crossing. Thus, there is normally an aircraft on the runway back-taxiing to the departure end or holding in position. In this event, the Gulf Coast Aviation aircraft had started its takeoff roll when its clearance was canceled.

“They were probably on a collision course,” Rubin said.

Rubin says he is very excited about winning the Archie League Medal of Safety, which he calls, a “really cool honor.” More importantly, he adds, it is validation of the importance to always say something if you see something.

“Whether you’re a trainee or a 25-year veteran, if you see something not right, you say it,” Rubin said. “When you do it, and you get the recognition, you think, ‘people are watching and they do appreciate what I’m doing.’ It’s just a really cool feeling.

“As human beings, we know what should be right and what’s not right, and the same thing with air traffic controllers. If it’s not right, or doesn’t look right, say something. The worst they can say is, ‘that’s how it’s supposed to be.’ But the best thing ever is if you can save dozens or potentially hundreds of lives.”

Hittner, Rubin, and Smart are the first winners of the Archie League Medal of Safety Award from ICT since Mark Goldstein received the honor in both 2005 and 2006. Additionally, the three ICT members won a quarterly NATCA Central Region Safety Award.

Watch the award presentation:

Highlights of this flight assist:

PODCAST: Listen as ICT member Hunter Rubin discusses how this event unfolded, and how ICT controllers handle their busy airspace, in this episode of The NATCA Podcast. View transcript of the podcast.

Eastern Region: Mark Dzindzio, Potomac TRACON (PCT)

Potomac TRACON (PCT) controller Mark Dzindzio played a key role in assisting Piper PA-28 pilot Karl Muller, who was having difficulty navigating in IFR conditions above the Shenandoah Valley in western Virginia.

Muller began flying in 2015 and earned his license and instrument ratings over the next two years. He had just joined a flying club in Harrisonburg, Va., near Shenandoah Valley Regional Airport (SHD), and bought a home nearby. On this day in late May 2020, he planned to fly up to his previous home airport, Hagerstown (HGR) and back to SHD. The first leg was uneventful. On the flight back, Muller filed an IFR plan.

“I wanted to descend and fly VFR along Interstate 81 (which connects Hagerstown and the Shenandoah Valley) at about 2,000 feet,” Muller said. “But my initial mistake was simply flying into the clouds at 5 or 6,000 feet on my instrument flight plan, at which point I could not descend and go VFR.”

At PCT, the COVID-19 pandemic was in its early stages and traffic was light. “There wasn’t much flight activity. Most things had been canceled,” said Dzindzio, who last year marked his 10-year anniversary at PCT after starting his career in 2009 at Manassas ATCT (HEF).

Muller’s flight needed special attention and an instrument approach into SHD. Conditions were windy. He was having difficulty flying straight and level and his unfamiliarity with both local approach fixes and using his onboard Garmin GPS sent him off course. By his own admission, fatigue led to confusion and made him doubt where he was.

Dzindzio vectored Muller to the localizer at SHD. But Muller was not able to pick it up or stay on the glideslope. At that point, Dzindzio told him to go around because it was not looking like a very safe approach. Additionally, Air Force Two was on their scope, and Dzindzio had a feeling it was going to be too much to handle combined. So the position was split and another PCT controller sat down to talk with Muller.

It was learned that Muller was inexperienced in IFR conditions, so the number of corrections, turns, and length of turns were limited in an effort to keep things simple and lighten Muller’s workload.

“Instead of trying to manage both the iPad and the cockpit Garmin, I made sure I put the controller first, did exactly what he said, and – although I did keep an eye on both the Garmin and ForeFlight – it finally felt like, ‘I can do this,’ rather than being confused,” Muller said. “It was almost a surprise when I popped out of the clouds because I was focused on doing exactly what he said. And once I popped out of the clouds, I was just joyful in telling him, ‘airfield in sight!’”

Muller, who credited the voices of Dzindzio and other controllers with having “a calming effect” on him, had the unique opportunity to thank the controllers during a virtual meeting last year.

“It means a lot because I get to say thank you,” Muller said. “It was life changing because they saved me in the clouds.”

Dzindzio initially wondered why he was chosen to receive the award. “It was a little surprising to be chosen,” he added. “It definitely was such a great result, of course, and we knew that there was absolutely a danger of the pilot not landing successfully. When he said he had the field in sight, it felt really good.”

Dzindzio is the fourth PCT member to win the Eastern Region Archie League Medal of Safety Award, joining Joseph Rodewald (2015), Matt Reed (2012), and Louis Charles Ridley (2010).

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Great Lakes Region: Bob Obma, Indianapolis Center (ZID)

During any normal shift in Area 2 of Indianapolis Center (ZID) on a mid-March Saturday afternoon, assisting the pilot of a Cessna 172 Skyhawk who encountered icing conditions would have required the same knowledge, calm professionalism, detailed checklist of tasks, and supreme focus that experienced ZID NATCA member Bob Obma brings to work.

But this particular Saturday afternoon shift, on March 21, 2020, was the first in which three areas at ZID were closed after positive COVID-19 tests. With uncertainty swirling as the nation began its descent into the throes of the pandemic, the challenges involved with handling an emergency situation – like this Skyhawk – increased.

“Quite possibly the craziest week of my life that I can remember,” said Obma, who had just been recertified three days prior to this shift after being off the boards for multiple years with a medical issue. “You’re walking down the hallway and you pass these areas with yellow police tape marking them off. All the lights are turned on but there’s no controllers. You could still see some random data blocks on the scopes. It just felt really strange.”

Traffic levels were still high. The closure of much of ZID’s airspace forced controllers to work on the fly and join together to come up with plans and make them work. There were re-routes around closed airspace, aircraft in Area 2 that are usually not worked in that lower altitude airspace (23,000 feet and below), and other situations that were not planned for.

“Everyone was already on high alert,” Obma said. “Their energy was already revved up.”

Dennis Tyner was piloting the Skyhawk. He departed Prestonsburg, Ky., headed for Lexington, Ky. He encountered icing conditions and requested a lower altitude from Obma. Unfortunately, because of the mountainous terrain, Obma was only able to get him down to 3,100 feet, which was not enough to get the ice off the aircraft. As an experienced pilot himself, Obma knew what Tyner was experiencing in trying to fly the aircraft. Obma declared an emergency for him before starting work to vector him around higher terrain and setting him up for an approach at an alternate airport in Morehead, Ky.

Morehead-Rowan County Airport was right next to Lexington ATCT (LEX) approach control airspace.

Obma said the situation required Tyner to quickly get on the ground due to the amount of ice on the aircraft. Tyner couldn’t descend and burn off the ice due to the minimum vectoring altitude, and couldn’t climb either. Time was critical.

Tyner called the Area 2 supervisor, Aaron Stone, after he successfully landed to express his gratitude. Stone said he could hear loud crashing noises in the background. Tyner told him, with a chuckle, that was the sound of the ice falling from his aircraft onto the apron.

This flight assist marks the third time Indianapolis Center members have represented the Great Lakes Region (NGL) in the 16-year history of the Archie League Medal of Safety Awards, all in the last three years. Nicholas J. Ferro and Charles Terry won the award in 2019, and Daniel Rak won in 2018.

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

New England Region: Dave Chesley, Boston TRACON (A90)

Late on a mid-summer evening, over the ocean and in the fog, pilot Lihan Bao was flying a short final ILS approach to Runway 24 at Martha’s Vineyard (MVY), her second time flying into that airport. The tower had just closed for the night. Shortly after her VOR receiver began to swing left to right, Bao saw a group of bright lights which distracted her. She turned left a bit to try to go back to the approach course but it didn’t work, and a few seconds later she and her passenger heard a noise. She had hit something.

Lihan was at 400 feet and started to lose directional control of the Cessna 172 (N677DM). She added full power right away and tried to bring the wings level. Then, she radioed Boston TRACON (A90) and declared an emergency. On the other end of the mic was someone perfectly qualified to assist her, eight-year veteran controller Dave Chesley, who is also an experienced pilot and flies his own home-built aircraft, a single-engine Murphy Moose, with his wife, Jody, who is also a controller (Boston ATCT, BOS) and pilot.

Chesley maintained a calm, reassuring demeanor throughout the entire incident. He guided Lihan with clear instructions as she diverted to Otis Air National Guard Base (FMH), which had a long runway, a 24-hour facility, and was reporting VFR conditions.

“He gave me headings and altitudes with the voice that made me believe we would survive,” she said.

Chesley works the Legacy Cape airspace in the South Area of Boston TRACON (A90), where he also serves as the NATCA area rep. He grew up in Maine surrounded by a wealth of aviation knowledge and experience. One of his grandfathers was a gunner and dive bomber in World War II. His other grandfather owned small planes and flew outdoor sports enthusiasts to spots in remote northern Maine to hunt and fish.

Lihan had departed with her friend from Caldwell Airport (CDW) in New Jersey. The initial weather report for MVY was VFR conditions but that changed while Lihan was in the air. She decided to land at Groton-New London Airport (GON) in Connecticut and filed an IFR flight plan for the second leg to MVY.

Chesley said it was a fairly normal approach. “It wasn’t until about a two-mile final that things changed,” he said. In one radar return, the aircraft had made a 90-degree left turn.

“I thought to myself at the time that this was either a bad radar return or something could be wrong,” he said. Two more radar returns confirmed the latter. Chesley could tell that Lihan wasn’t flying the published missed approach procedure. The turns, climbs, and descents were erratic. He made two attempts to reach her, with no response. Then came the emergency call and Chesley said Lihan reported they had struck something (later determined to be a tree, causing serious damage to the wing) and the aircraft was uncontrollable. “It’s certainly not the words you want to hear as a controller,” he said. “It’s one of your worst nightmares.”

“He could hear that my voice was shaking and tried to calm me down,” Lihan said.

Chesley knew that as a pilot, you train for emergency scenarios and you learn to never stop flying the airplane. He focused on assisting Lihan with just flying the airplane, maintaining a straight and level attitude, and getting to a safe altitude so they could then figure out their options. With the terrible weather at MVY, Chesley knew another landing attempt there was not the safest option. Low ceilings, fog, poor visibility: “The cards were stacked against us,” he said. Fortunately, to the northeast was FMH and its 8,000-foot runways.

“He told me he would guide me to an airport 15 miles away (FMH), which was VFR there with long runways, and I can land (at) any runway I want,” said Lihan, who was able to get control of the aircraft. “I applied full right rudder and full right aileron to keep my wings level.”

Others in the A90 operation assisted in coordination with FMH, allowing Chesley to concentrate on assisting Lihan. She made a soft landing at FMH “thanks to everyone’s help,” she said.

“A lot of times they say we’re fortunate in this industry that we don’t have to take our work home with us,” Chesley said. “I would agree 99 percent of the time but it’s these instances that you do take home and you do replay over and over in your head, wondering ‘what if I had said this, or what if I had done that’ and how it could have affected the outcome. Fortunately, I’m very thankful it turned out the way it did and hats off to the pilot for doing such a phenomenal job.”

Chesley is the third NATCA member from A90 to win the Archie League Medal of Safety Award, joining Jesse Belleau (2018) and Ken Hopf (2005).

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Podcast

Northwest Mountain Region: Byron Andrews, Joshua Fuller, Ryan Jimenez, and Michael Sellman, Seattle Center (ZSE)

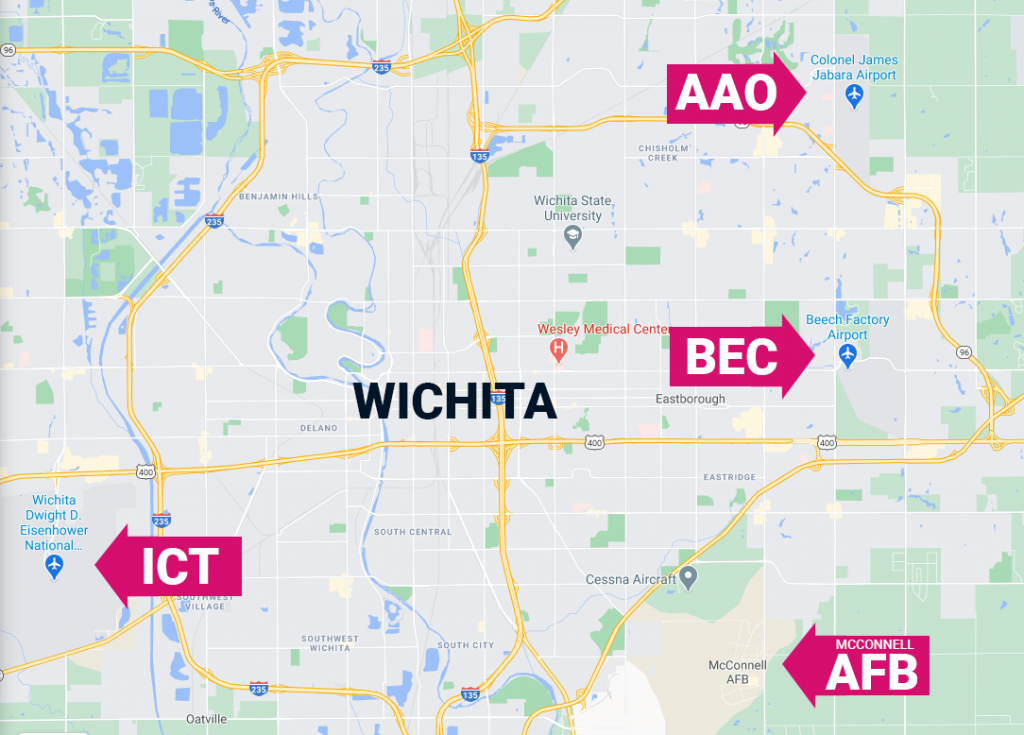

As Seattle Center (ZSE) member Josh Fuller’s shift was ending on the Saturday afternoon before Thanksgiving in 2019, a supervisor from Area C walked through Area B urgently looking for anyone with pilot experience. A VFR-rated Cessna 182 Skylane pilot in far northern Idaho, Tim Bendickson, had departed Boundary County Airport (65S) on what was supposed to be a 40-minute flight to the southwest back to his home airport in Priest River, Idaho (1S6). Instead, he immediately encountered fog and severe icing conditions, typical for that time of year, ending up in Canadian airspace.

Bendickson, knowing he could not find his own way back to the airport, called ZSE. “I just almost hit another mountain, I don’t know where I am,” he said.

Fuller grabbed his headset, went to Area C, and told the supervisor he had limited pilot experience but not in a Cessna 182. He plugged in. “My stomach was in my throat,” he said, “because I did not have any idea what we were getting into. My first thoughts were, let’s just get him on a heading and keep his wings level.”

Fuller spent the next two hours working with fellow ZSE members Byron Andrews, Ryan Jimenez, and Michael Sellman. It was an unforgettable team effort that saved the life of Bendickson, who was facing an array of challenges including disorientation that often leads to disaster for pilots. He was also 2,000 feet below the minimum IFR altitude. At ZSE, with 12 seconds between updates on their radar scopes, Bendickson’s position changed dramatically with each sweep. “Any adjustments we make, we have to wait 12 seconds to see if those adjustments work out,” Fuller said.

“Being in the control room, everyone could feel the weight of the situation,” Sellman said.

Sellman was working the low altitude sectors adjacent to where the emergency was occurring. It was a busy football Saturday, with Washington State hosting Oregon State in Pullman, Wash. Sellman worked to free up frequency space on the emergency sector (sector 8) by instructing other controllers to put any aircraft going to low altitude on his frequency. He said the airspace Bendickson was in is worked with non-radar procedures most of the time. Additionally, he said, “our radio coverage is pretty bad,” except for part of a valley where fortunately Bendickson was when ZSE first started to hear him. But that coverage was spotty when he was over the mountains.

Andrews was training a new controller on high altitude that day. He stopped training and ran over to the low altitude D-side position to assist Sellman and coordinated with high altitude controllers, approach controllers, and flight data. Jimenez worked with Sellman to split up initial coordination duties. He also took key steps to alleviate controller workload and frequency congestion. “We had to keep that sector as sterile as possible, to minimize any chance of interference,” Jimenez said. “We needed to keep Josh’s life as easy as possible in that situation.”

Perhaps the most harrowing part of Bendickson’s zig-zagging path above the mountainous terrain occurred near Scotchman Peak, near the Montana border. It rises to 7,040 feet above the town of Lake Pend Oreille, Idaho. Bendickson’s altitude, captured in three successive radar updates: 7,000, 7,100, and 6,900 feet.

It was clear at that point that Bendickson had no opportunity to go east, given the terrain and his ice-induced descent.

Next, Sellman, Andrews, and Jimenez all played a critical role in using a Washington Air National Guard KC-135 Stratotanker flight – Expo91 – inbound to Fairchild Air Force Base (SKA) in Spokane, Wash., to begin search and rescue instead of landing. The controllers used the flight to find VFR conditions and relay it to Bendickson.

Fuller told Bendickson, “November 2-2 Bravo, you’ve made it a long way so far, so thanks for hanging in there.” Bendickson replied, “Thank you so much!” The crisis was not over, but everyone involved started to have a much higher degree of confidence in a safe outcome. Expo91 reported that Bendickson, on his current heading, would break out of the clouds in 8-10 miles. Ninety minutes after his initial call to ZSE, he emotionally transmitted that he could see land. After ZSE shipped Bendickson to approach control for handling into Coeur d’Alene Airport (COE), east of Spokane, Wash., the relief was joyous and overwhelming.

“A couple of us unplugged and there was some applause in the room,” Fuller said. “It was kinda cool.”

“Thus far into my career, this was the craziest situation we’ve been involved with,” Jimenez said. “I just think it’s really remarkable that Josh was able to show up and plug into airspace that they are almost completely unfamiliar with. Everybody involved had one goal and we were singularly focused on that, trying to find Tim a place to land safely.”

At the 11th Annual Washington Air National Guard Awards banquet on Feb. 8, 2020, Col. Larry Gardner, 141st Air Refueling Wing (ARW) Commander, showcased what he called an act of heroism by the airmen from Team Fairchild. The crew of Expo91 included pilots Lt. Col. Mike Harris and Capt. Charles Roark from the 141st ARW and Senior Airman Kendall Bryant, a 92nd ARW boom operator.

Calling Seattle Center for help “saved my life,” said Bendickson, who has been flying for 10 years. “They were nurturing and just kept me calm and kept me focused on what my task at hand was. Everything boils down to what my instructor said which is, first and foremost, fly the airplane. That’s what I did.”

“This was an incredible thing to be a part of,” Fuller said. “These guys did one hell of an incredible job. Tim did a remarkable job just holding it together. He’s the one that actually fought for two hours while we coached.”

Watch the awards presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Southern Region: Marcus Troyer, Pensacola TRACON (P31)

It was like most any other ordinary summer afternoon in Pensacola, with a lot of weather, when Marcus Troyer plugged in for his shift at Pensacola TRACON (P31) shortly after 12:30 p.m. EDT. In the skies to the west, U.S. Coast Guard Lt. Commander Brian Hedges was the pilot and aircraft commander on an ordinary training mission in a newly-converted MH65E helicopter. But a short time later, Troyer and Hedges were joined in a search and rescue effort that was anything but ordinary and showcased the essential nature of their respective professions.

Thanks to their efforts, the life of the pilot of a Cessna 172 Skyhawk, Scott Jeffrey Nee, was saved after he crashed into the sandy bank of the Escambia River in a remote area of Jay, Fla., north of Pensacola near the Alabama border, and was seriously injured.

“They are heroes,” said the plane’s owner, Freddie McCall. “They saved a man’s life.”

McCall called the facility to report that he was missing an aircraft.

“We weren’t talking to the aircraft at the time,” Troyer said. “We went back and did a Falcon replay to try and see if we actually tagged him up or anything. We did not, so that complicated the situation.” Troyer had experience doing quality control work and was well versed on search and rescue situations.

McCall, who used his own aircraft to look for Nee, located the crash scene and reported that to Troyer, who was in his 12th year of his Federal Aviation Administration career – all at P31 – through this event before initiating a transfer to Houston Intercontinental ATCT (IAH) earlier this year. “I used all my knowledge that I had from working at Pensacola and tried to get Navy helicopters to respond, but most of them couldn’t do it because of fuel,” he said, adding that the heavy thunderstorms in the area posed many challenges. A LifeFlight crew was in Pensacola but had just completed a mission and was in a mandatory cooldown period.

Soon after, Troyer contacted Mobile ATCT (MOB) and asked if they were providing service to any Coast Guard helicopters. He did this because he knew that the Coast Guard has a base in MOB airspace. However, that base is used strictly for training and aircraft testing, not search and rescue. A MOB controller advised Troyer they were talking to a Coast Guard helicopter and he requested them to switch the communications to Troyer’s frequency. Troyer made contact with Hedges (pictured above), explained the situation, and asked if they would voluntarily attempt to respond to the crash site.

“I felt like if anybody was going to be able to do a rescue and get this pilot out of there, it was going to be the Coast Guard,” said Troyer, who spent the next 25 minutes vectoring Hedges to the crash site and helped get him around a strong line of storms. At that point, an EMS crew on the ground had reached the pilot and Troyer facilitated communications between them and Hedges.

“We had a very good crew but we didn’t have a rescue swimmer on board so theoretically we were not SAR (search and rescue) capable,” said Hedges, who has over a decade of experience as a Coast Guard pilot. He was joined on board by Lt. Commander Bob Lokar and Petty Officer James Yockey. Their base is the largest Coast Guard aviation training facility in the country. “This was the first search and rescue case in the MH65 Echo aircraft so it was kind of unique. We didn’t plan it that way but our aircraft had an all-new glass cockpit and brand-new weather radar, which actually helped us that day.”

Hedges said the unplanned SAR operation was made much smoother due to Troyer. “His demeanor, everything on the radio, was fantastic,” Hedges said. “He painted a perfect picture of where we needed to go, what we needed to do, and who was on scene.”

Once they reached the crash scene, Hedges said he had to keep the helicopter running at half power to prevent it from sinking into the soft sand on the riverbank. As it was, he said, the wheels were halfway down into the sand during the brief time he was on scene.

The crew soon took off with Nee and an emergency medical technician on board and headed to Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola. Troyer knew Hedges had never landed at that hospital before so he put him in touch with the LifeFlight pilot who was there and could walk him through the landing and any details he needed to know to arrive safely.

USCG Aviation Training Center Commanding Officer, Capt. W.E. Sasser, Jr., sent Troyer a letter of commendation for what he called Troyer’s “exemplary response.”

“The professionalism and expertise of your team helped my aircrew to safely navigate numerous hazards through the duration of the mission,” Capt. Sasser wrote. “Your controllers were directly responsible for saving a life. I commend your team for their hard work, dedication, and expertise! Bravo Zulu and Semper Paratus.”

After he left position following the event, Troyer said he went to his car to try and relax from the incredible adrenaline rush he was feeling. He said all he could think about was the condition of the pilot, and his desire to talk with Hedges to say thanks. Since the event, he and Hedges have talked several times and gotten to know each other. Troyer said he is appreciative to P31 colleague Dan Briscan for spearheading the effort to recognize him for this save, and had a suggestion for his fellow members who go through these types of events together as a team.

“Show your appreciation to your fellow brother and sister controllers,” he said. “We all say, ‘well, that’s just part of your job,’ but anytime somebody goes through it, the adrenaline’s rushing, people handle things a little bit differently. But talk to them after. Give them some praise.”

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Podcast: Below, hear Troyer and Hedges tell their story, and discuss their efforts to make this rescue mission a success, in an episode of the NATCA Podcast.

View a transcript of the podcast here.

Media: Watch here, a story from WEAR-TV.

Southwest Region: John (Randy) Wilkins and Christopher Clavin, Fort Worth Center (ZFW)

Fort Worth Center (ZFW) air traffic controller Randy Wilkins has worked enough general aviation traffic in his 13 years there to know that while he and his colleagues aim to provide the best support they can and the most information possible to pilots who encounter difficulty, ultimately, it’s up to the pilot to finish off a safe landing.

But Wilkins (pictured top left) is passionate about training and developing his base of knowledge in as many different ways as he can to be prepared for challenging situations. That includes researching air safety investigations in his spare time, looking at how past NATCA Archie League Medal of Safety Award-winning controllers handled situations, watching YouTube instructional videos of VFR pilots encountering IFR conditions, and learning about the dangers of pilot vertigo in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC).

“You watch a video and think, ‘well, what would I do? Would I know to say that? Would I know to think about this?’ So I really fall back on those replays,” said Wilkins, who said one of the most important things he learned from watching other Archie League Award event replays is the importance of being calm on the radio, as it helps keep the pilot calm and focused. “If I was a pilot, I would think, ‘if that was me, what would I want to know, and what would I want somebody to say to me before I did this?’ The worst thing you hear about is people getting disoriented and flipped upside-down. The likelihood of getting disoriented in clouds if you’re not used to it is pretty high.”

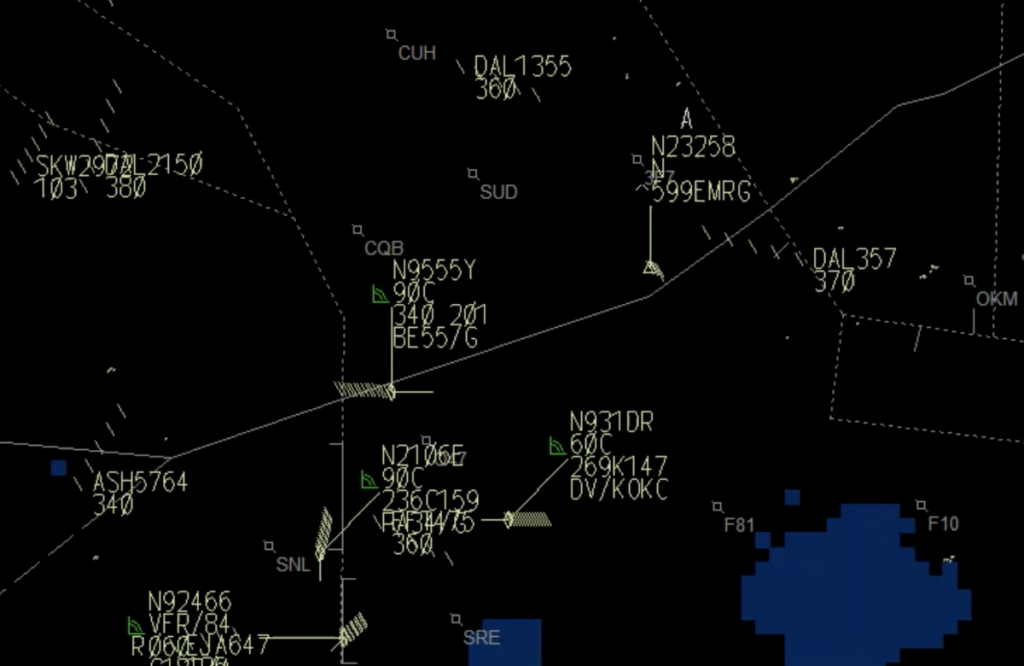

That was the situation a Cessna 150 pilot faced in Wilkins’s airspace as he flew in solid IFR conditions near the boundary of Kansas City Center (ZKC) airspace, between Oklahoma City approach control and Tulsa approach control. He was lost, definitely under stress, and sought help through the Guard radio frequency. He ended up talking to a Southwest Airlines pilot who was trying to figure out where he was.

Five years ago, ZFW began piping the Guard frequency into the operation. Wilkins says that alerted him to this situation. He got the pilot onto a ZFW frequency, brought up his location on radar, and gave the data block an EMRG designation for emergency.

“(Guard) is absolutely helpful in situations such as this. I think it’s very important and very useful,” said Wilkins, an Indiana native who graduated from Purdue. He started in engineering but later switched to Aviation Technology, Purdue’s CTI program.

The pilot was having trouble holding altitude and did not have the power to climb well. He was talking pretty well with Wilkins but then became frustrated and began to fly in circles.

At that point, fellow controller Chris Clavin (pictured top right), a Long Island, N.Y., native who began his career at ZFW three years ago, was working initially in the Ardmore sector near the end of his shift but heard the chatter on Guard. He sat down with Wilkins and the two controllers worked to find a place for the pilot to fly to and land safely.

“While Randy’s dealing with talking to the pilot, I was just trying to get the most up to date weather information that I could between Stillwater, Kansas City Center, Oklahoma City Approach, and Tulsa Approach to see if they had any guys going VFR in the airports around there,” Clavin said. “I was just trying to make sure that Randy didn’t have to do any coordination. It was my job to make sure he could focus on the pilot and I’ll take care of all the other stuff.”

The only good weather report was from the west side of Oklahoma City airspace, but the pilot was too far away to reach it with only ¼ tank of fuel remaining. Wilkins told him to focus on his instruments, don’t look out the window, and keep his wings level and airspeed up.

“You could see him going through the process of learning how to fly, either on his instruments or however he was doing it,” Wilkins said. “You could see him getting better and better at taking control of his aircraft. That might have saved his life – the 10 minutes he had to get used to flying in a manner like that, rather than saying, ‘I’ve gotta get through the clouds now.’ That’s how it looked to me.”

The landing spot was picked – Chandler Municipal Aiport (CQB), located near Interstate 44 between Oklahoma City and Tulsa. The ceiling was only 900 feet but better than other options. At that point, Wilkins and Clavin lost radio communications as the pilot descended beneath 2,500 feet. They put him on an advisory frequency, relayed information through another general aviation pilot, and waited for word that he landed safely.

“You don’t want to think the worst, but there’s other things going on in the sector that we had to take care of,” Clavin said. “It felt like 20 years before we finally got the update that he was on the ground.”

Clavin expressed gratitude at being selected as an Archie League Medal of Safety Award winner.

“After seeing previous years’ winners and looking at all of those events, it’s definitely an honor,” Clavin said. “I will be honest and say that, as the assistant, I don’t feel that I deserve nearly as much credit as Randy does. But I’m glad I was able to help and do anything I could.”

Wilkins says he looks at past winners with amazement and a “how did they do that?” wonder, but places high value on each event’s training value. He marvels in particular at the 2013 President’s Award-winning flight assist by Boston ATCT (BOS) controller Nunzio DiMillo that saved lives when DiMillo saw a Cirrus SR22 erroneously lined up to land on a taxiway occupied by a JetBlue flight.

“To be categorized like that is an honor, and I really hope that people can take it and learn something from it, because that’s really what this is all about,” Wilkins said. “It’s about honoring the controllers that did a good job, but I try to use it as a training tool to say, ‘here’s what happened and this is what you can do if you get into this situation.’ That’s what I really hope comes out of it.”

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

Listen as Fort Worth Center controllers Chris Clavin and Randy Wilkins help a Cessna pilot out of the clouds above Central Oklahoma, in this episode of The NATCA Podcast. Click here to listen | View transcript of podcast

Southwest Region: Larry Bell, Brian Cox, and Colin McKinnon, Fort Worth Center (ZFW)

Pilot and flight instructor Anise Shapiro and her student, Jouni Uusitalo (pictured below), were flying Uusitalo’s Piper PA-46 Malibu on a Saturday last spring from Hereford Municipal Airport (HRX), southwest of Amarillo, Texas, to Graham Municipal Airport (RPH), 80 miles northwest of Fort Worth, Texas. Halfway into the nearly 75-minute flight, they lost the engine for the first time in Shapiro’s 23 years of flying. At 14,500 feet and needing quick options, she declared an emergency to Fort Worth Center (ZFW) NATCA member Brian Cox.

Cox asked Shapiro the standard emergency questions of how many souls were on board and how much fuel was remaining. Shapiro responded, “We have two souls, and we have two female pups and four puppies.”

Cox, a 22-year veteran who has also worked at Kansas City Center (ZKC) and Denver Center (ZDV), knew this would be no ordinary day on position, but he was struck by how calm Shapiro was in the face of this urgent situation. Cox also has that trait, according to fellow ZFW member Colin McKinnon. “It’s definitely awesome that it was Brian working, because he’s probably the calmest guy in our building, certainly in our area,” McKinnon said.

The Malibu, nicknamed the “Starship Enterprise” by Uusitalo for its relative spaciousness for transporting dogs in their crates, was being used for a Pilots N Paws mission. Shapiro and Uusitalo flew several of these flights last year, each in West Texas. On this flight, the engine failure immediately put Shapiro into instructor mode.

“I practice it (engine out) all the time and run my students through it,” she said. “A lot of things are going through your mind. I think we were very fortunate to have two pilots onboard. I told him what to do, declared the emergency to get help, and immediately pulled the checklist out so we could start running through it all to see if we could get the engine restarted.”

Cox immediately set to work to find landing options. He was quickly joined by Larry Bell, a former accountant, who was the Controller in Charge for this shift, and McKinnon, a pilot, who was assigned to Cox’s D-side and pulled up the visual flight rules chart for Cox to use. Bell and McKinnon were both hired in 2012 and have worked at ZFW their entire careers.

“The first thing I was trying to do was determine where is the nearest airport because, unfortunately, where she was in a spot east of Lubbock is where there are not a lot of airports,” Cox said.

One was Harrison Field of Knox City, Texas (F75), which was at Shapiro’s 1 o’clock and 25 miles away. She had a visual, and an encouraging glide ratio report. Unfortunately, with the trademark strong winds of West Texas forcing a quicker loss of altitude than expected, Shapiro needed another option.

McKinnon took over the ZFW 49 high sector frequencies to help alleviate frequency congestion for Cox. McKinnon also helped identify the closest highway. Bell, a Texas Tech alum who often drives to the campus in Lubbock, was familiar with the area and knew it was Texas State Highway 114. But Shapiro said from the air, it looked less like a “highway” and more like a typical West Texas two-lane mostly dirt road, lined with fences and mesquite trees. She declined that as a safe landing option.

Shapiro and Uusitalo spotted a final option: An open wheat field with no trees or cattle that had just been cleared of hay. Cox gave her a phone number to call when she was on the ground to expedite the process of search and rescue. The landing was smooth. No injuries. Bell quickly found the coordinates of the landing spot and forwarded them to the operations manager. Help arrived about 20 minutes later and they even brought water for the dogs.

Shapiro said she could feel the ZFW team behind her, having her back. “Knowing that you’re not alone actually is more helpful as a pilot than anything,” she said. “They stayed super calm. The calmer each transmission was, the calmer I felt.”

McKinnon said he worked an aircraft with engine trouble a few months’ prior to this incident. “I had the same feeling of, ‘oh man, please, make sure she’s on the ground safely,’” he said. “I thought she did an exceptional job.”

“I think we all agree that if we have an aircraft land in a field, we all sit there afterwards and think, ‘what could we have done better?’” Bell said. “But in this situation, I think we made all the right calls.”

“I want to thank Larry, Colin, and Brian for being such outstanding ambassadors and representatives of the true definition of a team, a workforce, and professionals that stepped in to rise to the moment,” said ZFW FacRep Nick Daniels said. “I couldn’t be more proud. They make us all look good.”

Watch the awards presentation:

Listen to and watch highlights from this flight assist:

BELOW: Listen to Bell, Cox, and McKinnon discuss this event in an episode of The NATCA Podcast. | View transcript

BELOW: Listen to a podcast conversation with pilot Anise Shapiro. She describes what the experience was like and how she and Uusitalo and the six dogs they were transporting all escaped unharmed after landing safely in a wheat field.

Western Pacific Region: Michelle Bruner and Jamie Macomber, San Diego ATCT (SAN)

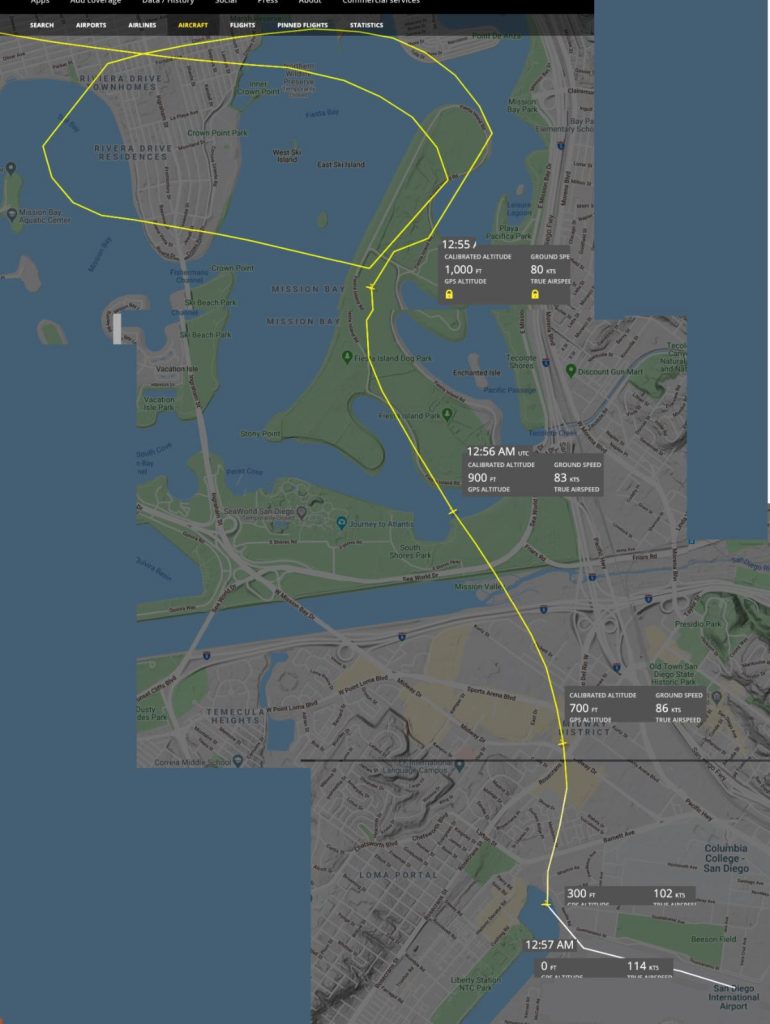

Duffy Fainer holds three skydiving world records and has encountered eight parachute malfunctions and one emergency ocean landing in 46 years of jumps. His first in-flight emergency in 15 years of flying airplanes, late in the afternoon of Wednesday, April 22, 2020, gave him a different kind of feeling. But he credits the calm, professional, expert handling provided by San Diego ATCT (SAN) NATCA members Michelle “Shelly” Bruner (pictured top left) and Jamie Macomber (pictured top right) with helping him to a safe, albeit nerve-rattling, landing.

Fainer’s home airport is Montgomery-Gibbs Executive (MYF, formerly known as Montgomery Field). He departed on his usual route of flight in his Grumman American AA-5A Cheetah, N365PS, heading west of the Miramar Naval Air Station airspace toward the Pacific Ocean. After Fainer crossed over Crystal Pier, located on the ocean just north of Mission Bay, he realized the throttle was not working properly. It was stuck at the 2,000 rpm point, which was enough to enable him to sustain level flight but it wasn’t going to let him climb. Fainer was at 800 feet at that point in a coasting climb that then took him to 1,200 feet but no further.

“I just felt dread because I knew most likely this was not going to resolve itself,” Fainer said. “I knew that I wasn’t in a good position to try and get back to Montgomery Field, which was six miles away. I was stuck at an altitude that I knew I would have had rising terrain on my way back and that didn’t seem like a good idea flying over houses and suburbs and buildings.”

So Fainer called SAN and was immediately soothed by Bruner’s familiar voice. “She said, ‘whatever you need,’” Fainer said, “which gave me a lot of confidence and sense that somebody was there backing me up despite the fact I was in the cockpit all alone with my sad little airplane.”

“I knew something was up on his first transmission,” said Bruner, the daughter of a Navy mechanic who spent more than five years in the Army before starting her Federal Aviation Administration career 11 years ago. She’s been at SAN for the last 10 years. She noted that Fainer, a professional announcer and host, has a very familiar voice and callsign.

“We’re very familiar with him coming into the airspace but he always calls with all of his requests all at once,” Bruner said. “So this time, when he just called me with his callsign, I’m like, ‘OK, this is going to be different.’ I think instantly the adrenaline started kicking in. I had to figure out what was going to happen, what’s my plan – A, B, and C.”

On that day, in that month, just weeks after the start of the COVID pandemic, traffic was light at SAN, which worked in Fainer’s favor. But it still required the experience of the tower crew to safely handle this emergency.

Once Fainer said he needed to come in, Bruner and Macomber worked swiftly. Anticipating a possible conflict with normal IFR departure traffic off runway 27, Bruner proactively assigned a heading to SkyWest Flight 3378 to deconflict with Fainer. She also issued a go-around to United Flight 1869, which was on a mile final. Macomber handled the declaration of emergency with the airport and handled coordination with adjacent facilities and the fire crews.

“I think at that point, you’re just listening to what’s going on around you and picking up the loose ends; the little bits that need to be done,” said Macomber, who has also been at SAN for 10 years after working at Oakland Center (ZOA) for the first two years of her career. “Shelly sent the United (flight) around, so I called and let everybody know this guy’s going (around) and why he’s doing it, and then it was about clearing as much room and taking as much of the kind of paperwork part of it off of her as much as possible.”

The rpm gauge started to drop aboard the Cheetah and Fainer didn’t know how long the aircraft would sustain itself in flight. He had to make a decision before it was too late to glide anywhere. Beneath him was Fiesta Island, just three miles north of SAN. It has a two-mile stretch of sand that terminates into hard-packed dirt where it meets the water.

But Bruner had a better idea: She offered him an uncommon opposite-direction landing on runway 9, saving Fainer time and altitude.

“When she said runway 9 was available, and I was looking at 27 – which was another mile and a half to two miles away if I was going to approach it from that direction – it gave me an option I wasn’t really considering,” Fainer said, “but my hesitation was I didn’t want to tie up their nice big airport. I didn’t want to be ‘that guy’ that left a big smoking hole in the middle of their runway.”

He needn’t have worried. Macomber recalled a similar experience when a military Beechcraft T-34 lost an engine offshore and they had to bring them in to SAN for an emergency landing on runway 9.

Fainer didn’t know the extent of the problem at the time, a detached throttle bearing, which attaches the throttle cable to the carburetor arm like a trailer ball and hitch. All he knew with one mile to go was that he wasn’t sure if he was going to make the airport and if he did, he wasn’t sure how he was going to stop the aircraft.

At 140 miles per hour and downwind, Fainer killed the engine over the Engineered Material Arresting System (EMAS) before the numbers of runway 9, and put the plane into a steep sideslip bank, figuring that sooner or later it would run out of airspeed. He floated for a good mile down the runway. “I was wondering when it was all going to end,” he said. Finally, it did. He put it down and exited at the 7,500-foot mark.

Fainer (left) said that if he had attempted to return to MYF and tried that same maneuver he used to land at SAN, “I would have ended up in the In-N-Out Burger on the other side of the (Cabrillo) freeway.” He repeated one of the important lessons from this incident for other pilots that he wishes to share: Don’t worry about where your car is, or your hangar; worry about landing safely. “If you’re gonna have a drama you want to go to the longest runway, and have as many services waiting for you as possible,” he said.

“We’ve seen a lot of episodes lately where pilots overflew perfectly good airports with the intention of trying to get elsewhere and it didn’t end well for them. That’s one thing where aviators could do better. And the other thing is we’re typically afraid of, or intimidated by, the big Class Bravo airports and don’t want to infringe or impose or be a burden. I would certainly encourage aviators, especially after my incident, to ask for help and expect that controllers are going to make getting you down safely as their first priority.”

Bruner said she has gone to the Archie League Awards banquet 6-7 times and watched the playbacks of winning events closely. “You always hope that when that situation comes along, that you will be that calm voice; that you will be that helping hand to that pilot,” she said.

Added Macomber: “In those moments, your priority is just, ‘everything I have to do to make sure this person is safe, let’s do that.’”

Fainer, who grew up under the approach path to runway 24 left at Montreal-Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport, sparking a love of air traffic control, said he relishes his interactions now with ATC.

“Half of the fun of flying for me now is having a professional and cordial communication with the controllers and making my flight successful in that regard,” Fainer said, “not just landing safely but knowing I had a good communication with all the controllers en route.”

Watch the award presentation:

Watch and listen to highlights from this flight assist:

PODCAST: Listen below as Fainer, Bruner, and Macomber discuss this event.

Federal Contract Tower: Brad Burtner, Pompano Beach (PMP)

NATCA charter member Brad Burtner retired from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) on Jan. 3, 2008 after three decades of working traffic at four different facilities. Like many other retirees, Burtner headed to Florida, but he didn’t hang up his headset or put away his Union membership card.

Instead, two days later, Burtner started a new chapter as a Federal Contract Tower (FCT) controller at Pompano Beach ATCT (PMP). Four years later, he worked to organize the controllers to choose NATCA to represent them, adding to a growing list of the Union’s FCTs, which currently totals 116. That same year, Burtner started his six years of service on NATCA’s National Organizing Committee.

In late 2019, it was something Burtner did on the job that has earned him a new round of respect and admiration. NATCA this year is excited to announce the addition of a new category for FCT saves to join the nine geographic regions in the 16th annual Archie League Medal of Safety Award program. The first FCT winner is Burtner and NATCA will be honoring him and his fellow 2020 award winners on Aug. 11 at the 18th Biennial Convention in Houston.

Burtner worked at Cincinnati ATCT (CVG) from 1986 to his FAA retirement date after spending his first decade in the FAA at New Orleans-Lakefront ATCT (NEW), New Orleans Moisant ATCT (MSY), and Lake Charles ATCT (LCH). He said it was an easy decision to continue working at an FCT.

“I still enjoy my job and I like the camaraderie at work,” said Burtner who also serves as both PMP FacRep and Southern Region Alternate Vice President representing FCTs. “Everybody gets along great. It’s fun to work there.”

Late on a typically clear weekday morning at PMP in December 2019, Burtner was working local control and had four aircraft in the pattern. One was N955Q, a Beechcraft N35 Bonanza, which Burtner says flies in 1-2 times daily.

“You sit in the tower for a year or two and there’s no events,” Burtner said. “You’re busy with traffic, but it gets to be routine.”

But on this day, with this aircraft cleared to land on runway 10, something was off. “It didn’t look right, so I put binoculars on,” Burtner said. The aircraft was over the approach lights and in the flare, the transition phase between the final approach and the touchdown on the landing less than 10 feet above the ground, ready to touch down. That’s when Burtner noticed the landing gear was up and immediately issued a go-around.

The pilot was able to throttle in, pull up, reestablish the aircraft in the pattern, and manually lower the landing gear. He returned and landed safely. Afterwards he called the tower and advised that he had an armature problem that caused the gear malfunction. He said the go-around instruction saved the aircraft.

Donnie Snyder, the Chief Executive Officer of Buy, Fly, Sell, LLC, the company that owns the aircraft, was very thankful for Burtner’s quick actions. He visited the tower to personally thank Burtner and the staff and present Burtner with a special framed certificate. It reads, in part, “It is my honor to present this Recognition of Excellence letter to Bradley Burtner for his exemplary actions on this day. Furthermore, I commend the entire ATC staff at KPMP. They are one of the best in Florida.” Snyder also wrote that “Brad’s actions prevented damage to our aircraft, runway closure and all the other unpleasant events that follow an aviation incident.”

Robinson Aviation, Inc. (RVA) operates PMP. Its Area II Manager, Bruce Bivins, wrote a letter of appreciation to Burtner. “It is this special attention to duty and quick action that allows the system to have the safety record it enjoys,” Bivins wrote. “It is always a pleasure to learn employees’ vigilance and attention to detail has helped keep the flying public safe, and it gives us the opportunity to say ‘thank you’ from RVA and the users of the system. On behalf of Robinson Aviation (RVA), I would like to commend you on your performance.”

Burtner said he feels very honored to receive the first Archie League Medal of Safety Award for FCTs.

“It’s always nice to be recognized,” Burtner said. “I’ve been working for NATCA since three or four years after its founding (in 1987). It’s always nice being recognized for things by your Union and know people appreciate your work and know you’re still doing a good job.”

Watch the award presentation:

Listen and watch highlights of this flight assist:

The NATCA Podcast: Listen as Brad talks about this event and his career (below). | View transcript of this interview.

Honorable Mention

CENTRAL REGION

Darrell Bott, ZKC

Patrick James, ZKC

Philip Lapoint, ZKC

Javier Salmon, ZKC

Derrick Willis, ZKC

EASTERN REGION

Bronson Burriss, EWR

Randy Throckmorton, EWR

Joanna Remigio, JFK

Gaetano Chetta, PHL

Adam Cohen, PHL

Matthew Bode, ZNY

Zachary Clark, ZNY

Joseph Lanzetta, ZNY

Richard Rogers, ZNY

Richard Soucheck, ZNY

Christopher Stolworthy, ZNY

Dominick Vernice, ZNY

Orville Whyte, ZNY

GREAT LAKES REGION

Zachariah Schneider, MSN

Micah Bales, RFD

Jason Maurer, RFD

Wayne Short, RFD

Nicholas Derado, ZID

Steven Sexton, ZID

NORTHWEST MOUNTAIN REGION

Justin Simpson, D01

Hunter Panetti, HIO

Edward DeLisle, P80

Jeremy Prus, P80

Joseph Laporte, ZLC

Christopher Watson, ZLC

SOUTHERN REGION

Nicholas Klose, BNA

James Williams, CLT

Michael Driscoll, DAB

Sean Caldwell, ILM

Derek Hartman, ILM

Benjamin Olkowski, ILM

Cameron Purser, ILM

Craig Monroe, SDF

SOUTHWEST REGION

Joshua Kwapy, ACT

William Buvens, HUM

Shane Ooten, SHV

Christopher Alexander, ZFW

Ryan Baird, ZFW

WESTERN PACIFIC REGION

Michael Holbert, CRQ

Michael Mallette, CRQ

John Macchiaroli, LAX

Kelsey McKendrick, LGB

Clinton Meche, LGB

Kyle Vercautren, LGB

Nicholas DiBenedetto, SNA

Nicholas Roth, SNA