Jan. 13, 2017 // New York Center’s Newcomer with Some Serious Skills

This story was published by the Federal Aviation Administration this week on MyFAA and Focus FAA.

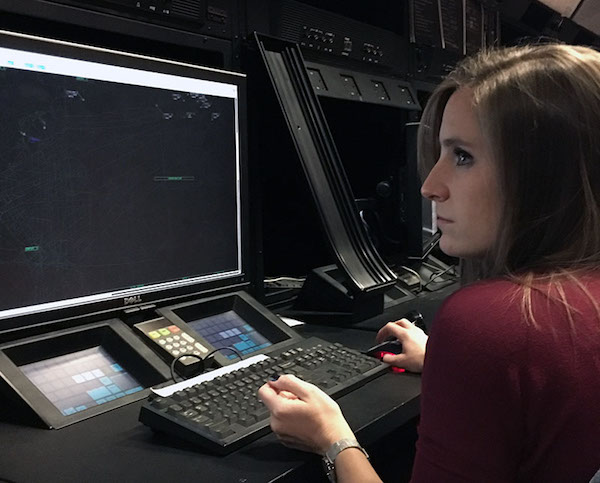

Heather Hruz had only been certified as an air traffic controller at New York Center (ZNY) for about a year when the realities of the job tested her skills twice in a matter of days. She proved both times that she is up to the challenge.

In the first emergency situation, Hruz used advanced technology to converse quickly with an Air France pilot who was flying over the ocean with a passenger in distress. She gave the aircraft priority to descend to a lower altitude and then to land. Eleven days later, Hruz helped ensure the safe emergency landing of a military aircraft that had to divert to a closer airport.

“She is a hard worker who I would describe as the ideal employee to have on your crew,” Operational Supervisor Jacob Issac said of Hruz. “Her knowledge base in aviation is on par with veteran [controllers] of 25-plus years.”

An Indiana native, Hruz earned a professional flight degree from Purdue University in 2010. But with commercial airlines still furloughing pilots after she graduated, she opted to get a master’s degree in aviation and aerospace management and pursue a career as an air traffic controller.

Hruz started her training at the FAA Academy in April 2011. A friend suggested that she list New York as her top choice to work if she wanted a job quickly, and sure enough she received an offer to work at ZNY two weeks after applying. “It was very, very quick and worked out in my favor,” she said.

Hruz “checked out” as a certified controller in September 2015 and quickly impressed managers at the facility. Issac said she is an “ideal employee” who not only does quality work in separating aircraft every day but also suggests valuable solutions as operational challenges arise. She demonstrated her professionalism on position twice this past September.

The first incident on Sept. 18 involved an Air France aircraft flying in non-radar airspace over the Atlantic Ocean. The aircraft was equipped with Controller Pilot Data Link Communications technology, which enables pilots and controllers to interact via text messages.

The pilot used the technology to request a lower altitude. “In the middle of the ocean, that is not exactly normal,” Hruz recalled, so after granting the request, she asked the pilot why he made it. The pilot explained that an asthmatic passenger was having trouble breathing and that a doctor on board thought a lower altitude might improve the situation.

The pilot did not declare an emergency, but Hruz alerted her supervisor to the situation just in case it worsened. Within about 15 minutes, it did. The pilot asked for a direct approach to Martinique Aimé Césaire International Airport in the French West Indies.

Hruz updated her supervisor with the latest development and called the controller who would work the aircraft next to arrange for an ambulance on the airfield.

“They landed with no problem, and the passenger was all taken care of,” Hruz said.

The CPDLC technology enhanced the controller-to-pilot interactions, cutting the time of each piece of the conversation by up to several minutes. Capt. Francis de Rozario and First Officer Christophe Pernoud expressed their appreciation in a note to Hruz.

“One can say you just did your job,” they wrote. “But to know that somewhere, someone is waiting to facilitate and help you whatever request you make is very nice.”

Hruz was on position as the assistant controller on Sept. 27 when a more challenging situation required her calm demeanor. Seven EA-6 electronic warfare aircraft and two KC-135 refueling tankers were flying a military mission under the Altitude Reservation System. One EA-6 had been scheduled to return before the other aircraft, but the pilot of a different EA-6 contacted the center.

“At that point, we wondered what was going on,” Hruz said. She told a supervisor about the situation as fellow controller Steven Schraner tried to gather more information. The pilot initially requested a direct approach to Atlantic City International Airport but soon asked for the distance to Bangor International Airport instead, with his voice sounding more urgent.

Schraner learned that the plane’s fuel pressure had malfunctioned. As he communicated with the aircraft, Hruz contacted Boston Center to explain the situation. The destination changed twice more after the pilot declared an emergency – first to Hanscom Field in Bedford, Mass., and eventually to Otis Air National Guard Base near Falmouth, Mass.

Each time, Hruz gathered the relevant weather details, approach routes and runway lengths, conveying the information to the pilot through Schraner. The airport in Falmouth was about 60 miles closer than Hanscom Field, and it offered runways of more than 8,000 feet and instrument landing systems for a precision approach in bad weather.

Schraner handed the flight off to a controller at Boston Center.

“I was watching his radar hit the whole time,” Hruz said, adding that Schraner later called the control tower at the base to confirm a safe landing. The aircraft only had about 20 minutes of fuel by that time.

“With calm and deliberate reaction to an intense situation, both controllers were able to assist the aircraft to a safe emergency landing,” Issac said. “Their actions certainly helped mitigate a situation that could have turned out much worse.”

Hruz didn’t become a controller to help pilots through trying circumstances, but she is glad to have played a part in two such instances early in her career.

“You feel good about your job, and you feel like, ‘I’m glad I was sitting there today so that we could help this pilot.’”